In 19th-century America, letter writing was serious business. Knowing how to express one’s thoughts on paper effectively was as important then as knowing how to operate a smartphone is today. Ken Burns’ landmark Civil War documentary would have been impossible to create without the vast treasure trove of letters, diaries, and journals that Burns was able to tap. The documentarian and his associates acknowledge this in the introduction to the book The Civil War, which has been selected as a companion book for this year’s One Book, One Philadelphia.

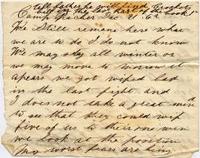

Notice how this letter by Josh Chamberlain, a Union officer at the Battle of Fredericksburg, put us in the center of the action:

But out of that silence … rose new sounds more appalling still … a strange ventriloquism, of which you could not locate the source, a smothered moan … as if a thousand discords were flowing together into a keynote weird, unearthly, terrible to hear and bear, yet startling with its nearness; the writhing concord broken by cries for help … some begging for a drop of water, some calling on God for pity; and some on friendly hands to finish what the enemy had so horribly begun; some with delirious, dreamy voices murmuring loved names, as if the dearest were bending over them; and underneath all the time, the deep bass note from closed lips, too hopeless, or too heroic to articulate their agony.

One would like to think that future generations of Americans will record the critical events of their times with both the passion and precision that Chamberlain brought to the letter above, but I doubt it. The sad truth is that the internet, together with the unindicted co-conspirators Facebook and Twitter, has killed the art of letter writing in our country. The consequences of this untimely death, both large and small, deserve our attention. For centuries, people have cherished love letters and thoughtful notes sent to them by spouses, partners, and family members. These are the kind of messages that people keep their entire lives. My guess is that relatively few Millennials have such a collection. Those born in 2016 or later will likely wonder what all the fuss was about.

Historians have always depended on both personal and professional letters to really understand the tone, tenor, and nuances of individual lives—and the life of an entire society. Real-like letters like those fictionalized in Cold Mountain between Ada and Inman tell us far more than the history books about what life was like—what people felt—during the Civil War.

Presidents and other key federal officials may be forced by law to archive their emails, but the rest of us will not. I can’t raise this subject without thinking of my late father, Sam Levinson, a proud son of the Bronx, who was born in 1921. Between the time Sam volunteered to serve in World War II and the day that he actually reported for duty, he received a letter from his favorite high school teacher. He kept that letter for the rest of his life. I know why: As one would expect, she offered encouragement and support—but it goes beyond that. Love and concern shine through in every single line. She thought he would come back, but just in case, she told him everything she wanted him to know, in the event that they never saw each other again. Future historians, bereft of such personal documents, face a long and difficult road.

Desperate times call for desperate measures. Could the current situation actually bend the arc of history in ways that we do not expect? During the Middle Ages, professional scribes wrote letters on behalf of those who could not compose their own. Their counterparts currently do a brisk business in India and a host of other developing countries today. Might we eventually see the rebirth of a profession once seen as worthless as elevator operators and watch painters here in the U.S.? I wouldn’t rule it out. Perhaps those of us who truly care about letters can make a last stand in the nation’s classrooms and job centers. Can you think of another dying art form with a more urgent claim on our attention and support?

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.