The art and artifacts of Queer women artists archived in the Free Library's Special Collections — specifically, the Print and Picture Collection, the Theatre Collection, and the Children's Literature Research Collection — testify to the existence and artistry of these women and continue to inspire today.

Above, artist Violet Oakley shows her likeness and shows off her confident handling of a notoriously difficult medium: watercolor. This Oakley self-portrait from 1912 lives in the Free Library’s Print and Picture Collection. Oakley was a painter, muralist, and stained-glass designer who lived from 1874 to 1961, and made Philadelphia her home after attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. At PAFA, Oakley met Edith Emerson, an artist in many media, Violet Oakley’s life partner, and the keeper of her legacy after her death. Emerson became curator of the Woodmere Art Museum in 1947 and served as its director till 1978, and Woodmere is one of the best local places to become acquainted with Oakley’s work.

Best known for her murals at the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg, the work of Violet Oakley — like that of another great Queer American muralist, John Singer Sargent — has a dramatic theatricality with a hint of the numinous. The small watercolor above shows another side of Violet Oakley. Though it bears the look of something done swiftly and with little deliberation, Oakley’s confident rendering of her collar’s blazing white, her hat’s soft felt, and her open nonchalance announces an artist who is in full command of texture, color, and expression.

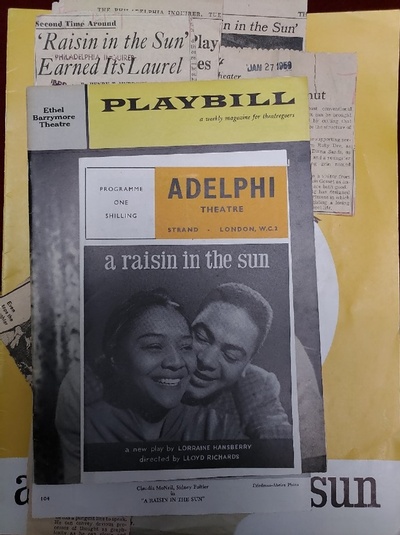

The folders of programs, photos, and newspaper cuttings that spread across the table I was working at when I asked to see the Lorraine Hansberry objects in the Free Library’s Theatre Collection, for a Pride Presentation I put together before Covid, amazed me with the joy and triumph they radiated. Every review cutting I read of Hansberry’s 1959 Raisin in the Sun was ecstatic, the production photos were full of life, and the yellows and oranges and bold graphic design of the playbills announced the advent of a meteoric theatrical talent. My surprise was due to my habit of thinking of this great Black playwright in the context of her early death from pancreatic cancer. Hansberry’s death, in 1965 when she was 34, took a brilliant writer, activist, and developing Queer intelligence from the world. Hansberry’s death mirrors, for me, the death of the great Queer playwright — and contemporary of Shakespeare — Christopher Marlowe, in a pub fight in 1593, when he was 29. (Both writers left lasting consolations in the form of at least one indisputable masterpiece: for Hansberry, A Raisin in the Sun, for Marlowe, Dr. Faustus.)

I learned from reviewing the materials relating to Lorraine Hansberry in the Free Library’s Theatre Collection that the magnitude of Hansberry’s intellectual endowment and genius for writing is powerful enough to upstage even the tragedy of her early death. One of Hansberry’s letters to the lesbian publication The Ladder from 1957 can be read on the online primary source reader of Bronx Community College of the City University of New York.

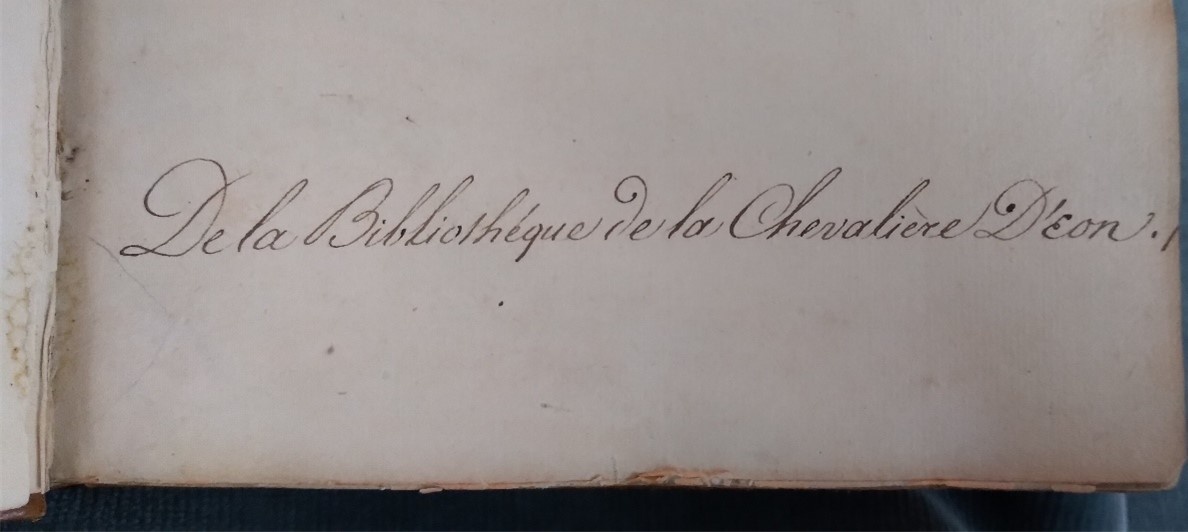

"From the Library of the Chevaliere d’Eon" is written, in French ("De la Bibliotheque de la Chevaliere d’Eon") at the beginning of a handwritten book of favorite poems, or commonplace book, on a shelf at the Rosenbach Museum — and with a few vowels, the Chevaliere d’Eon proclaims and asserts her womanhood. French is a language in which the definite article (in English the, in French Ia) has male and female variants depending on the gender of the noun that follows it. The Chevaliere d’Eon, as written by the Chevaliere d’Eon, is the title of a woman. And though English has no female variant for the word knight, in French, a knight is understood to be a woman if an e is added to the word Chevalier, making it Chevaliere.

Though many in France in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were perplexed by the Chevaliere — who had lived as man for the first 49 years of her life, dressed as a woman when spying in Russia for the king of France in her middle years, and lived as a woman ever after — the Chevaliere insisted she had always been a woman. That the Chevaliere had to explain and demand that her identity be recognized makes her experience parallel to that of many Queer and trans people today. In the Chevaliere’s case, it was only after 14 months of negotiation, and by a judgement of the Court of the King’s Bench and a special order of Louis XV, that in 1777 she was legally recognized as a woman. To this day, multiple institutions and media outlets continue to spell her title without the final e.

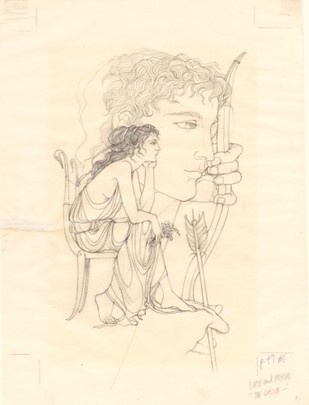

The drawing above is by Trina Schart Hyman, an American children's book illustrator who was born in Philadelphia in 1939 and lived til 2004. The drawing, graphite on tracing paper, is an illustration of the mythological figures Cupid and Psyche that Hyman did for the book Two Queens of Heaven by Doris Gates (New York: Viking Press, 1974). Hyman presented it to the Free Library in 1975, where it now resides with the Children’s Literature Research Collection. Hyman’s instantly recognizable style, with its frankness and clarity, has been a treasured companion of many bookish childhoods; in the image above, the power of her line is striking. Hyman’s command of her pencil is languid and vigorous. Its unique grace beguiles the eye. As manifest in the folds of Psyche’s dress, Hyman’s line recalls the whorls of a fingerprint — making this drawing in Free Library Special Collections a fitting place to end a Pride Month article focused on Queer woman artists and ancestors whose work — and identities — continue to inspire beyond their lifetimes. All of these materials, and much more, are available for patrons to see in our Special Collections. A portion of our materials are available to view online in the Digital Collections. Otherwise, you can contact one of our collections and make an appointment.

To learn more, visit the pages of the Print and Picture Collection, the Theatre Collection, and the Children’s Literature Research Collection.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.