Blog Articles

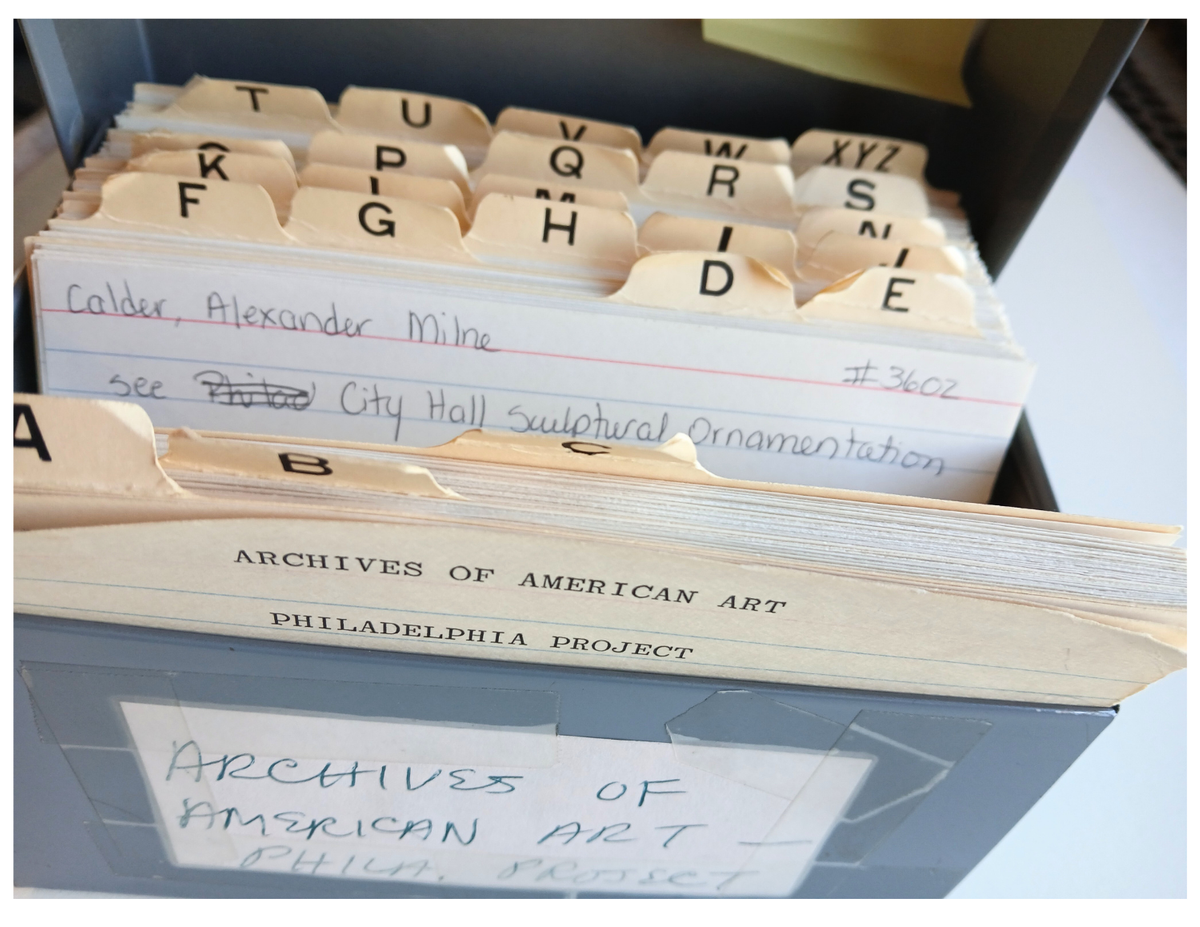

Starting in 1955, the Archives of American Art began documenting Philadelphia-related art material for the Philadelphia Arts Documentation Project . This epic undertaking has involved working with… continue reading The Philadelphia Arts Documentation Project

By written by Natasha S. November 4, 2025

Across the city, community organizations, mutual aid groups, and neighborhood volunteers are stepping up to provide free meals, groceries, and fresh produce through food distribution sites,… continue reading Find Local Food Aid Amid the SNAP Funding Freeze

By written by Administrator November 3, 2025

We are grateful for these new titles arriving on our shelves this fall! Young Children (up to 2nd Grade) Benjamin Grows A Garden by Melanie Florence Benjamin is ready to help his mother plant… continue reading New Titles Coming to the Free Library in November

By written by Rachel F. October 30, 2025

The Field Teen Center is partnering with Common Sense Media to bring free digital literacy workshops for teens to the Free Library throughout the 2025–26 school year. Digital… continue reading Teen Digital Literacy Workshop Series Starting This Fall

By written by Yona Y. October 28, 2025

The Free Library of Philadelphia is expanding its six-day service by adding Saturday hours at nine additional neighborhood library locations . By October 25, 2025, a total of 41 libraries will be… continue reading Additional Saturday Hours Roll Out at Neighborhood Libraries

By written by Administrator October 24, 2025 2

General Election Day is Tuesday, November 4, 2025 , and 34 of our neighborhood libraries will serve as designated voting locations. Polls are open from 7:00 a.m. until 8:00 p.m.… continue reading 34 Libraries Will Serve As Polling Places for the November 4, 2025 General Election

By written by Administrator October 24, 2025

[ Editorial Note: The Free Library’s Literature Department is Parkway Central Library’ s home for language learning and the study of global literature. Department librarians are… continue reading Yiddish Children’s Literature from the Secular Yiddish Shuls of the Workers’ Circle and the IWO

By written by Administrator October 22, 2025 1

Once upon a time, you were a child, and you loved a book. It was a classic, one that perhaps a beloved aunt or teacher had shared with you. You cherished this book, and now as an adult you want to… continue reading Classic Children’s Books Re-read, and What to Read Instead!

By written by Administrator October 17, 2025

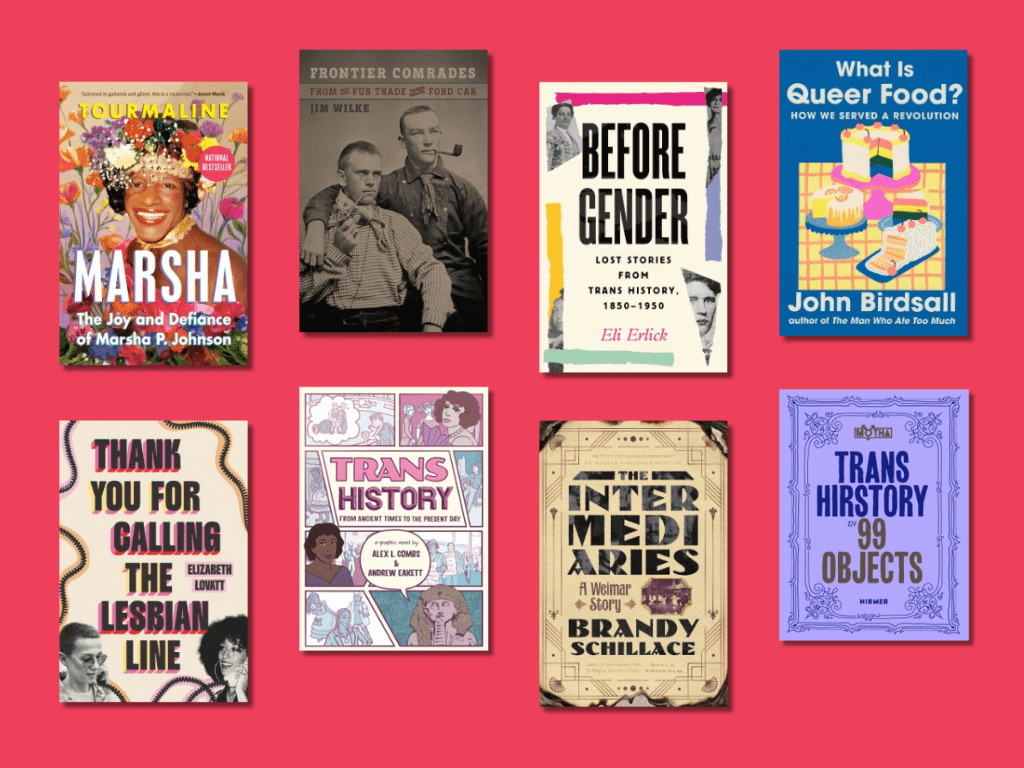

October is LGBTQ+ History Month. These historians show that gender and sexual diversity have always been a part of the fabric of humanity. For many, LGBTQ+ history begins in 1970, when seemingly… continue reading New Titles Perfect for LGBTQ+ History Month

By written by Shelley R. October 16, 2025

Want to get a Free Library card , but unsure how to go about it? Look no further for everything you need to know about becoming a patron of the Free Library of Philadelphia! Who is eligible for a… continue reading How To Get a Free Library Card

By written by Administrator October 14, 2025 2

Join us at Parkway Central Library for a special storytime series celebrating the many languages of Philadelphia! Each storytime in this series will be bilingual, highlighting different… continue reading Languages of Philadelphia: A Bilingual Family Storytime Series

By written by Bridget G. October 6, 2025 1

Free college prep workshops are returning to the Free Library for Fall 2025! Field Teen Center hosts these FREE workshops in partnership with The Alexander Advantage and … continue reading Register in Advance: Free College Prep Workshops Coming This Fall

By written by Yona Y. October 6, 2025 1

Leaving a federal government role and embarking on a new career journey is an understandably daunting experience. With the right tools and strategies, you can position yourself for a successful… continue reading Tips and Resources for Federal Workers in Transition

By written by Administrator October 6, 2025

The Free Library Music Department and Consonant Collective team up to bring lathe-cut vinyl records to the masses! A new program is dropping at Parkway Central Library… continue reading Cut Your Own Vinyl Record With DIY Discs!

By written by Jane L. October 6, 2025 2

Join the Northeast Regional Library for a sweeping introduction to South Asia. This five-part series, taking place late October to early December, introduces the history and culture of one… continue reading An Introduction to South Asia Lecture Series at Northeast Regional Library

By written by Rebecca R. October 1, 2025 2

The Penguin Random House Banned Wagon is coming to Philadelphia for Banned Books Week and will make stops at Northeast Regional Library on Friday, October 10, and Parkway Central Library on… continue reading Join the Banned Wagon for Banned Book Fest!

By written by Katrina W. September 30, 2025

These new titles are coming to the Free Library in October! Young Children (up to 2nd Grade) Día de Muertos by Jacque Jours Discover the meaning of Dia de Muertos and learn how children all… continue reading New Titles Coming to the Free Library in October

By written by Rachel F. September 30, 2025

The Community Quilt Circle Workshops , featuring Colombian textile artists Nicolle Valencia and Shanise Barona, are a three-part workshop happening on Thursdays from 2:30 to 4:30… continue reading Add to Our Community Quilt for Hispanic Heritage Month

By written by Saloua A. September 29, 2025

The Free Library of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Zoo are collaborating again to present the annual Animal Tales series at Charles L. Durham Library . On the… continue reading Popular Animal Storytimes Return to Charles L. Durham Library

By written by Christina B. September 29, 2025 1

The Academy of Natural Sciences and the Free Library of Philadelphia are old friends. For over 100 years, they have existed across from each other on the Benjamin Franklin… continue reading The Academy of Natural Sciences Free Pass Program Returns

By written by Joe S. September 26, 2025 3