This is the seventh in a series of posts highlighting major figures in jazz history who were from Philly (even if most ended up in New York City). A virtual book discussion of Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original by Robin D.G. Kelley, hosted by the librarian who is writing this series, will take place on Thursday, April 22 at 7:00 p.m. Every one of the bolded album titles below can be streamed for free with your library card via Alexander Street’s Jazz Music Library database.

Edward Lee Morgan was born in 1938 and raised at 2035 W. Madison Streets in the Tioga neighborhood of North Philly, where his parents Otto and Nettie had settled after moving up from South Carolina and Georgia, respectively. His oldest sister, Ernestine, played organ and led the choir at the Second Baptist Church near Broad and Erie. Ernestine also loved jazz, and often took her younger brothers, Jimmy and Lee, to the Earle Theater at 11th and Market to see Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and many others.

Ernestine bought Lee a trumpet for his thirteenth birthday, and the youngster immediately demonstrated prodigious talent. He was first tutored by trumpeter and bandleader Donald Wilson, who lived a block from the Morgans. In addition to learning the mechanics of the horn, Morgan would join other young musicians in Wilson’s home for sessions where they would take turns improvising along with records. Morgan himself was an avid collector and bassist Reggie Workman (best known for his work with John Coltrane, the subject of the first Philly Jazz Legends post) recalled that Morgan "had an incredible record library and all of us would get together every week to listen to his records," often leading to jam sessions.

As a young teen, Morgan participated in free extracurricular musical education provided by the Philadelphia School District. He spent Saturday mornings studying at the Widener School at Broad and Olney, where his first trumpet teacher was a man named Hy Wynn, whose main gig was as the trumpeter for the Philadelphia Ice Capades. Morgan also frequented many "rehearsal bands"—ensembles made up of players too young for the bar scene, who would get together to rehearse in living rooms and community centers. Years later a peer recalled seeing Morgan playing the music of one-time Philadelphian Dizzy Gillespie in the Tommy Monroe rehearsal band: "That was the first time I heard Lee play jazz and he was, at 14 years old, absolutely awesome."

Morgan’s older siblings attended Simon Gratz High School, a short walk from home. Morgan, however, convinced his parents to let him travel across town to the Jules E. Mastbaum Vocational High School in Port Richmond, where he could focus on his musical development. Mastbaum’s music program was led by Ron Wyre, the former director of the Annapolis military band. Wyre immediately recognized Morgan’s potential and recommended him to join the prestigious Philadelphia All-City High School Orchestra. Morgan dropped out after little more than a year, however, because, as a friend from Mastbaum put it, "it really wasn’t his scene."

Morgan’s scene was bebop, and his obsession with it was all-consuming. Another Mastbaum classmate recalled an early morning assembly interrupted by an argument between Morgan and his best friend, not about girls or sports or clothes, but about chord changes. The classmate remembered Morgan insisting, "What are you talkin’ about man? Here’s a dime. Go buy yourself some soul. That change is wrong. You want to play a C ninth!"

Outside of school, Morgan frequented the jazz workshop started in 1954 by Camden-based radio DJ Tommy Roberts, held at the Heritage House, a community center at Broad and Master, which now houses the Freedom Theater. Running from 4:00 to 6:00 p.m. on Fridays, the workshop featured musicians who were in town for evening engagements and gave them a chance to perform for, teach, and even socialize with up-and-coming Philadelphia players. Attendees over twenty years of age were actually turned away! Another participant remembered that "Chet Baker played there one day, and Lee came up and played—you know, skinny, scrawny, little Lee—and blew Chet Baker completely out of the room." Even allowing that Baker might not have brought his A-game to an afternoon jam session with teenagers, it’s astonishing to think that a fifteen-year-old could have "cut" the guy voted Best Trumpet in the previous year’s Downbeat Magazine critics poll.

At Heritage House, Morgan also met Clifford Brown, the brilliant trumpeter who had recently moved to West Philadelphia from his native Wilmington, Delaware. Morgan would visit Brown’s home, where the two would descend to the basement and work on music for hours on end.

Another weekly session was held at Music City, an instrument store at 18th and Chestnut. "They would bring guys in from New York to play," a peer recalled, "and they would have the young guys sit in with them. If you played pretty good, you always ended up with some kind of gig." The ambitious young Morgan excelled at finding professional engagements, leading ensembles that played dances, fraternity and sorority parties, and even down in Atlantic City. These bands were comprised mostly of players he had met at the Heritage House and Music City workshops, including an astonishing number of future giants, including Archie Shepp (subject of the fifth Philly Jazz Legends post), Henry Grimes (subject of the sixth), McCoy Tyner, Odeon Pope, Jimmy Garrison, Spanky DeBrest, Sonny Fortune, Reggie Workman, Ted Curson, and Bobby Timmons.

Morgan graduated from Mastbaum in June of 1956, and his career blasted off in just months. The first catalyst for his success was tragic: just a week after Morgan’s graduation, his mentor Clifford Brown was killed in a car crash. Brown’s death, at just 25 years of age, pushed Morgan to continue his mentor’s legacy. The death of the hottest young trumpeter in jazz also led record execs to look for the next big thing—a role Morgan would be more than happy to fill by the end of the year.

The second catalyst came a month later when drummer Art Blakey was bringing his group the Jazz Messengers to town for an engagement at the Blue Note at 15th and Ridge. The Messengers were undergoing personnel shake-ups, in part inspired by their Philly gig. Bassist Wilbur Ware remembered, "Now, I didn’t want to go to Philly, because I had heard that the police were so tough on addicts or people they thought were addicts, and if you had scars on your arm, you’d go to the penitentiary." The PPD’s approach led Ware and trumpeter Ira Sullivan to stay in New York, and Blakey to scramble for replacements. He chose Morgan and his friend, bassist Spanky DeBrest, as rising young stars of the scene, and the pair played to sold-out audiences for two weeks with the Messengers. Following this major increase in profile, Dizzy Gillespie offered Morgan a first-chair trumpet seat in his big band, one of the most prominent in jazz. On October 26, Morgan debuted with Gillespie at the Academy of Music at Broad and Locust, on a bill with Billie Holiday (subject of the second Philly Jazz Legends post). In just months, he had ascended from the floors of frat parties to the stage of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

In November of ‘56, Blue Note Records gave Morgan his debut date as a leader, Lee Morgan, Indeed!, driven by the hard swing of drummer Philly Joe Jones (subject of the third Philly Jazz Legends post). For the most Philly-centric track, check out "Reggie of Chester", written by Philadelphian Benny Golson. While your humble librarian-blogger has failed to confirm that the title refers to Reggie Workman’s ties to our urban neighbor to the south, he can say with confidence that the eighteen-year-old Morgan’s solo demonstrates a fiendish blend of virtuosity and laid-back confidence.

For the next decade and a half, Morgan released two, three, or even four albums per year—just including those under his own name! An accounting of his prolific work as a sideman, including 27 albums with the Jazz Messengers, would require a separate post.

Here are some Philly-focused highlights of Morgan’s output:

- The Cooker (1957) – featuring Philadelphians on drums (Philly Joe Jones) and piano (Bobby Timmons), and the first album to include Morgan’s original compositions.

- Lee-Way (1960) – on which Morgan’s quintet stretches out soulfully on four long songs, two by the great Philadelphia-raised composer Cal Massey.

- The Sidewinder (1963) – an unprecedented commercial hit for a jazz record in the ‘60s, which reached #25 on the Billboard charts, and became the biggest selling album in Blue Note Records history.

- Search for a New Land (1964) – the wistful title track of which is your humble librarian-blogger’s favorite Morgan composition.

- Cornbread (1965) – on which Morgan demonstrates his growing skill as a composer, having written four of the five tunes.

- Delightfulee (1967) – which includes a tune Morgan composed in celebration of the newly independent nation of Zambia, featuring a fleet solo from West Philly's McCoy Tyner on piano.

- Live at the Lighthouse (1970) – the last album released while Morgan was alive, which includes two compositions by bassist and Philly-native Jymie Merritt, including the gorgeous, introspective "Absolutions".

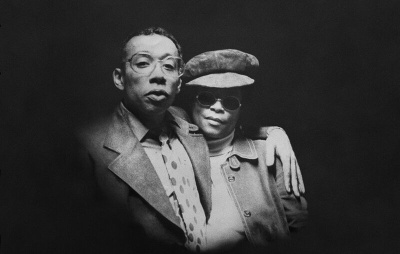

The idea of absolution is worth holding close when examining the end of Lee Morgan’s life. An enthusiastic substance user since his teens, Morgan began to spiral out of control in the late 1960s, to the detriment of his personal life and professional output. He was taken in by Helen Moore, a jazz enthusiast whose apartment had for years been a beloved place for musicians to get a hot meal before or even after a gig. The two became romantically involved, she became his manager, and she took his last name—though they never officially married.

One frigid February night in 1972, Helen showed up at a concert Morgan was playing at Slug’s Saloon in New York’s East Village. She confronted him about a woman he was with (he was, in fact, cheating on her), he had her removed from the club, and she came back in and shot him. He bled to death before an ambulance could make it through the snow.

The fantastic documentary I Called Him Morgan is structured around audio of Helen being interviewed just a month before she passed away in 1996. There isn’t space in a blog post to answer why Helen Morgan killed her common-law husband, if an answer is even possible. It’s clear in the documentary that many of Morgan’s closest friends believe that Helen saved his life in the years before she took it. Perhaps it’s best to use the tragedy as a reminder that people shouldn’t be forever judged by their actions at their worst moments. Helen Morgan was paroled after a few years and moved back to her native North Carolina in 1978 to care for her aging mother. She lived out her last two decades active in her community and church, going by Helen Morgan until the day she died.

This essay would not have been possible without the research of Jeffery S. McMillan, published as "A Musical Education: Lee Morgan and the Philadelphia Jazz Scene of the 1950’s" (Current Musicology, 2015).

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.