This is the third in a series of posts highlighting major figures in jazz history who were from Philly (even if most ended up in New York City). A virtual book discussion of Wishing on the Moon: The Life and Times of Billie Holiday by Donald Clarke, hosted by the librarian who is writing this series, will take place on Thursday, August 20 at 8:00 p.m. Every one of the bolded album titles below can be streamed for free with your library card via Alexander Street’s Jazz Music Library database.

Our first two entries profiled two of jazz history’s household names: John Coltrane and Billie Holiday. This third blog post covers a player who was anything but obscure, being one of the most recorded drummers in jazz history. But casual Philadelphia jazz fans might not realize how frequently they’ll see our city’s name in sobriquet form if they look at the personnel on many classic records.

Joseph Rudolph Jones was born in 1923 in his family’s Germantown home on Rittenhouse Street, just east of Germantown Ave. When his father passed away a year later, his mother went to work as a domestic servant for a wealthy white family in Chestnut Hill. The Jones’s moved frequently, ending up at 19th and Columbia Ave (now Cecil B. Moore). In the 1930s and early 1940s Jones spent some time at Simon Gratz, Benjamin Franklin, and Central High Schools, as well as a whole lot of time getting schooled in the thriving Columbia Ave jazz club scene.

Jones came from a musical family. His mother taught him piano and his aunt played saxophone professionally in an all-female ensemble. His first drum teacher was James "Coatsville" Harris, nicknamed for the central PA steel town of his birth. Young Joe was also an enthusiastic tap dancer. Tap was a popular form of creative expression among Black youth at the time—Jones never studied it formally, only learning in the street. This complex rhythmic footwork informed his percussion style, and later in his career, he would sometimes delight audiences by mixing a bit of tap into his shows.

In 1944, Jones entered the history books for the first time, but for a reason that had nothing to do with music. He was among the first seven Black men hired to drive for the Public Transportation Company of Philadelphia (the predecessor to SEPTA). In response, the all-white PTC union went on strike, causing a wartime transit crisis. President Roosevelt sent 5,000 federal troops to Philadelphia to stop the white supremacist strike. As a result, just weeks after his 21st birthday, Jones became a local face of integration as the first Black driver of the 23 trolley, the longest public transit route in the city, running from Chestnut Hill to South Philly. Legend has it that when passing Columbia Ave, Jones would sometimes stop his trolley and run inside a club to play a number. Your humble librarian-blogger and regular SEPTA-rider loves a good jazz legend, but he finds it exceedingly hard to picture a trolley-full of Philadelphians tolerating such a delay.

By 1947, Jones was regularly traveling to New York to play, as well as to discuss music with Max Roach. Though one year Jones’s junior, Roach served as a mentor, a position he’d earned by playing and recording constantly since his teenage years with the likes of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and everyone else present at the birth of bebop.

In an interview later in life, Jones said that Roach was once in Philly during this era and called Jones up, but Jones had to work that day driving a grocery truck. Not dissuaded, Roach rode along and two of the most influential percussion stylists of the Twentieth Century spent the day driving around Philly delivering fruits and vegetables, just so they could get the time to talk music.

Jones would soon take the advice of Roach and others and relocate to New York. There he was given the name he was thereafter known by—Philly Joe Jones—to distinguish him from the great Kansas City drummer, best known from the Count Basie Orchestra: Papa Jo Jones. For decades he would be central to bebop and the scenes and styles that grew from it, developing his sophisticated approach to rhythmic arrangement on hundreds of recordings led by many of the greatest artists of the era.

Here are some highlights, all available via the Jazz Music Library with your library card.

On the Clifford Brown Memorial album, Jones forms a rhythmic bedrock with his frequent partner, bassist, and South Philly native, Percy Heath. This 1953 date was the 22-year-old Brown’s first as a bandleader, just three years before the brilliant trumpeter’s untimely death. The album is actually a compilation of two recording dates, the other with Pittsburgh native Art Blakey on drums, giving the listener the chance to contrast the percussive styles of two giants of hard bop from opposite ends of our state.

In 1955, Miles Davis assembled what was later called his "first great quintet," including Jones and Philadelphian John Coltrane on tenor sax. In just two days, the band produced four modern jazz classics: Cookin’, Relaxin', Workin’, and Steamin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet. Commenting on the album name, Davis later said "After all, that's what we did—came in and cooked." This may have been true in another sense of the word "cooking." Davis and Jones were also partners in heroin addiction during this era, known for scoring and fixing together when on tour.

In 1956, Jones appeared on Sonny Rollins' classic Tenor Madness. The album opens with the only recorded duo between Rollins and Coltrane, with the eponymous "madness" drawn out by Jones’s perfectly placed "bombs" (spontaneous accents on bass drum or snare, in reaction to the soloist).

1958 was a banner year for jazz and Jones played on an astonishing number of great records. Lee Morgan’s The Cooker was recorded when Morgan, a graduate of Port Richmond’s Mastbaum Vocational Tech, was not yet old enough to drink. It features Jones with fellow Philadelphian Bobby Timmons on piano and Miles Davis Quartet alum Paul Chambers, who grew up in Pittsburgh. The album opens with "A Night in Tunisia," composed by Philadelphian Dizzy Gillespie, kicked off by Jones’s expressive work on the toms.

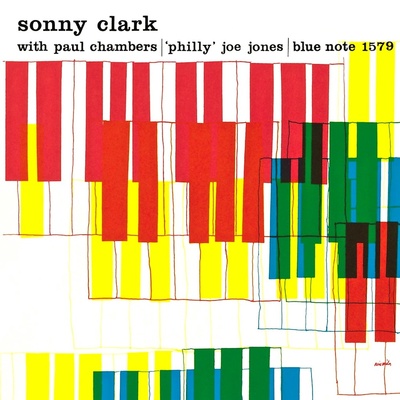

The self-titled Sonny Clark Trio (1958) finds Jones and Chambers backing piano whiz Clark, born and raised in Herminie, Pennsylvania. For the compact expressivity of the piano trio setting, you can’t do much better than this all-PA band’s absolutely smoking version of "Two Bass Hit," co-written by Gillespie.

If your tastes tend towards larger groups, check out vocalist Abbey Lincoln’s It’s Magic (1958), which features a dream team of a backing band, including Jones and tenor saxophonist Benny Golson, a Philadelphian who Jones had been playing with since his teens. Check out how Jones makes 3/4 time swing delicately on the haunting album closer, "Little Niles."

Jimmy Smith’s Softly As a Summer Breeze (1958) finds Jones swinging behind Smith, a native of Norristown, PA. If you’re like your humble librarian-blogger, your primary association with Smith’s instrument—the Hammond B-3 organ—is mellowing out over a city-wide special at Bob & Barbara’s, watching the Crowd Pleasers led by the late lamented Nate Wiley. Smith’s records from this era are the genesis of that sound.

Jones joined a Chicago-focused band on Johnny Griffin’s Way Out! (yes, 1958, but this is the last one). Listen to his solo on album opener "Where’s Your Overcoat, Boy?" to hear how subtly but powerfully he could translate the drum rudiments into an expressive language all his own.

Elmo Hope’s The All-Star Sessions compiles a fantastic handful of recordings from 1956 through 1961. A brilliant pianist and composer, Hope was a close friend and peer of Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, but never gained their success. Jones is the one constant on all tracks, joined by either Percy Heath or Paul Chambers on bass. The tenor saxophone role is Philly all the way: Coltrane on the earlier dates; Percy’s brother Jimmy Heath on the later ones.

Jones backed trumpet phenom Freddie Hubbard on Here to Stay (1962), which starts with "Philly Mignon," a tune Hubbard named for Jones. The "head" melody is nearly half generated by the drums, a remarkable tribute to Jones’s skill at making the kit a melodic instrument. Also worth noting is that everyone else playing on the album was a member at the time of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, with Jones here filling Blakey’s spot.

For Interplay (1963), exploratory pianist Bill Evans put together a remarkable quintet including Jones and Percy Heath. Check out the title track for a textbook example of Jones driving the band from the back seat, switching up what jazz musicians call the "time feel" under each soloist.

Philly Joe Jones, the consummate sideman, did occasionally step out in front as a bandleader. A few of these records, none of them his best-known, will serve to end this long list, which represents only a fraction of the classic albums Jones appears on. On Drums Around the World (1959), he leads complex arrangements played by a larger ensemble, credited as Philly Joe Jones Big Band Sounds. Blues for Dracula (1958) would be a normal hard bop album but for the addition of Jones doing a truly bizarre Bela Lugosi imitation as "the bebop vampire." Showcase (1959) is your humble librarian-blogger’s favorite record with Jones as leader. Check out his composition "Joe’s Debut" to hear him translating bebop’s byzantine harmonic twists into a tasty melody that goes down smooth with the help of perfectly paired percussion.

This blog post is indebted to the graduate research of Dustin Mallory published as “Jonesin’: The Life and Music of Philly Joe Jones”.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.