This is the fifth in a series of posts highlighting major figures in jazz history who were in some sense from Philly. Every one of the bolded album titles below can be streamed for free with your library card via Alexander Street’s Jazz Music Library database. The librarian writing this series will host a virtual discussion of the documentary Milford Graves: Full Mantis on Tuesday, December 8, at 8:00 p.m. The documentary is available stream free with a library card on Kanopy, and a major exhibit on Graves’s life and work is currently on view with free admission at the Institute for Contemporary Art

Archie Vernon Shepp was born in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in 1937. After World War 2, his family moved to Philadelphia, settling in the Brickyard neighborhood of East Germantown. In a recent interview with The Philadelphia Inquirer, Shepp remembered that "there was a factory that made bricks nearby, and it did carry that as a metaphor... a really tough neighborhood... tough times, and you had to learn to be tough. And there’s a certain beauty in that brutality. If you outlive it, you can express it."

Shepp was first exposed to jazz by his father, a Navy Yard worker, and young Archie was soon playing banjo, piano, clarinet, and saxophone. At age 12, he and childhood friend and jazz-legend-to-be Reggie Workman got the chance to see their hero, Charlie Parker, at the Met at Broad and Poplar. In that same Inquirer interview, Shepp recalls seeing Parker outside the gig with a white date. "Even the bravest Black man wouldn’t dare to be on the street with a white woman... He seemed to have no fear."

Shepp attended the now-shuttered Germantown High School where he developed an interest in literature and theater, which he went on to study at Goddard College in Vermont. From there, he moved to New York where he formed the New York Contemporary Five, a group heavily indebted to the rhythmic and harmonic revolutions of the "free jazz" of Ornette Coleman, and which included Coleman’s musical partner Don Cherry on trumpet. Archie Shepp and the New York Contemporary Five (1964) is an ebullient set recorded live at the Jazzhus Montmartre in Copenhagen, a place that was more amenable than most American clubs to the innovations creatively rending apart the jazz tradition.

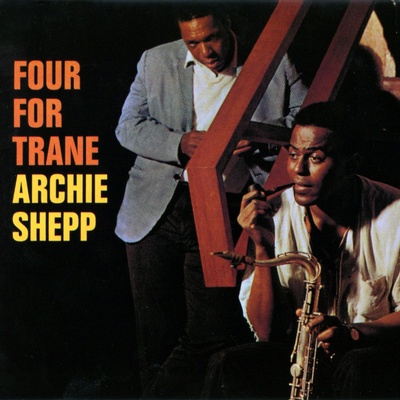

In New York, Shepp also sought out fellow Philadelphian John Coltrane. A decade older than Shepp, Coltrane’s influence had loomed large when Shepp was coming up in the Philly scene. Throughout the 1960s, Coltrane took on many musicians as disciples, though he was always just as open to learning from the younger players. He admired Shepp’s playing and composition so much that he personally interceded to get Shepp a deal with his label, Impulse Records. On Four for Trane (1964), Shepp pays tribute to his mentor, but in a way befitting an artist who believed the highest form of flattery is not imitation but inspiration. Shepp and trombonist Roswell Rudd rearranged four of Coltrane’s best-known tunes and used them as launchpads for new sonic excursions. Check out their reimaging of Coltrane’s gorgeous tribute to his first wife, "Naima," with dense re-harmonizing of the melody and Shepp’s bluesy wails, alternately brittle and fierce.

Shepp named his second album on Impulse Fire Music (1965), which was one of the terms coming into use to describe the fearsome playing epitomized by late Coltrane and his acolytes like Shepp, Pharaoh Sanders, and Albert Ayler. Throughout his carrer, Shepp refused to be pigeonholed though, and the album leads off not with the sonic conflagration suggested by the title but with a snappy horn arrangement indebted to the Afro-Cuban jazz made popular in large part by fellow Philadelphian Dizzy Gillespie. Shepp’s writing, arranging, and bandleading always played with this tension between the jazz tradition that he knew and loved, and the new expressive possibilities of horns played like the world was burning—which it seemed to be in 1965. Recorded just weeks after Malcolm X’s assassination, the piece "Malcolm, Malcolm, Semper Malcolm" opens with a Shepp recitation that, like his music, manages to be both poetically elliptical and cuttingly direct.

Shepp was relentless in his desire to expand the sonic scope of the music labeled "jazz." The title track of On This Night (1965), dedicated to W.E.B. DuBois, blends 20th Century classical dissonance with the open spirit of improvisation, featuring operatic vocals and Shepp himself on the piano. He tickles the ebonies and ivories again on "Sylvia" from Live in San Francisco (1966), moving from sparse dissonance to a ragtime feel, back to dense harmonic clusters and then into a ballad. Similarly, the opening track of Mama Too Tight (1967) at first seems like it’s going to be an entire LP side of high-octane collective improvisation, but periodically touches down with irreverent but lovely readings of tunes by Duke Ellington and Tin Pan Alley composer Irving Mills. On all of these albums, Shepp demonstrated that, just as he would not be constrained by the harmonic and rhythmic limitations of jazz before 1960, he also would not be constrained by a narrow vision of what it meant to be an avant-gardist during this revolutionary decade.

Like many jazz musicians of the 1960s, Shepp was drawn to the percussion of Africa and the African diaspora outside of the United States. The Magic of Ju-Ju (1968) brings this to the forefront with its side-length title track, on which Shepp wails evocatively over four percussionists playing talking drums and rhythm logs, as well as the standard jazz drum kit. Shepp’s intimations of Africa are always forward-looking, as is made explicit on Kwanza (1969), with "New Africa", as well as the head-nodding funk of "Back Back," both of which summon the spirit of the slogan of Shepp’s sometimes collaborators in the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music: "Great Black Music, Ancient to Future."

Moving into the 1970s, Shepp continued to incorporate Black popular music forms into his searching compositions, though in a way that was fundamentally different from the popular jazz-rock fusion of Miles Davis and others. Shepps’ syncretic style owes as much to the theater as to the dance floor. (Simultaneous to his music career, Shepp wrote plays, several of which were produced by the pathbreaking and award-winning Chelsea Theater Center.) The clearest example of this is Attica Blues (1972), on which Shepp processes the Attica Prison uprising and its murderous repression with tracks that could be heard as scenes as much as songs: the title track is a furious throw-down; "Blues for Brother George Jackson" is a tense exposition; "Ballad for a Child" is a rare moment of calm. Each of these scenes is set by clearly identifiable pop music styles, all while being unsettled by creative writing, arranging, and playing.

After one more Impulse album, the gospel-infused The Cry of My People (1972), Shepp’s discography is little represented on the Jazz Music Library. A nice exception is Live in New York (2001), which for the first time in thirty years reunites Shepp with Roswell Rudd, his trombonist and arranging companion for much of the 1960s, alongside other top-tier players from that era.

To do justice to Shepp’s insistence on innovation, as well as his disregard for the silos of genre and generation, it’ll be best to end with something not in the Jazz Music Library collection, but free to stream on Bandcamp. Just last year, at the age of 83, Shepp collaborated with the rapper Raw Poetic (who is Shepp’s nephew, as well as a native of Germantown) and the producer Damu the Fudgemunk, to create Ocean Bridges (2020). This wasn’t a case of hip hop sampling, but rather a full-fledged studio collaboration between the younger men and an octogenarian not content to rest on his considerable laurels. Check out "Tulips," on which Shepp’s horn dodges between the rhymes and sixty years of Black musical innovation cohere into one expression of creative freedom.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.