This is the sixth in a series of posts highlighting major figures in jazz history who were in some sense from Philly. Every one of the bolded album titles below can be streamed free with your library card via Alexander Street’s Jazz Music Library database. The librarian writing this series will host a virtual discussion of the documentary Milford Graves: Full Mantis on Thursday, December 10, at 8:00 p.m. The documentary is available to stream free with a library card on Kanopy, and a major exhibit on Graves’s life and work is currently on view with free admission at the Institute for Contemporary Art (check their website for up-to-date COVID restrictions).

This entry in the Philly Jazz Legends series covers the least "legendary" subject yet: a musician who, until 2005, had released only one album as a bandleader. But from the mid-1950's to the late 1960's, Henry Grimes held down the bass role on an astonishing variety of pathbreaking albums, and in the 20th Century. . . well, no spoilers—unless you already read the photo captions!

Born in 1935, Henry Alonzo Grimes grew up at 17th and Carpenter. He attended Chester A. Arthur Elementary and Barrett Junior High, both in South Philly. His parents played a variety of instruments and, in a 2009 interview, Grimes recalled that they had both once played professionally. But by the time young Henry could remember, they were cooking and cleaning for the Horn and Hardart chain of automats.

In junior high, Grimes encountered a generation of South Philadelphians who would go on to be esteemed jazz musicians, including Bobby Timmons, Ted Curson, and the brothers Jimmy, Percy, and Albert "Tootie" Heath. He next attended Port Richmond’s Mastbaum Technical High, a magnet school where he could focus on music, studying alongside trumpeters Curson and Lee Morgan (subject of the phenomenal documentary, I Called Him Morgan). Grimes had been primarily a violin player until age 15, when he was first given access to a bass at Mastbaum. A quick study, he rapidly took over a bass chair in the all-city orchestra, and was ultimately accepted to New York City’s Julliard School, the most prestigious conservatory in the country.

Heading north to Julliard in 1952, Grimes played orchestral music and studied with Fred Zimmerman, the principal bassist for the New York Philharmonic. All the while he was moonlighting, doing R&B and jazz gigs. At a club just across the river from Philly in Pennsauken, NJ, he was heard by baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, who hired him and with whom he first appeared on record. Just out of school, Grimes’s jazz career experienced a meteoric rise such that at 1958's Newport Jazz Festival, at just 22 years old, he appeared as the bass player for a staggering six separate groups: Mulligan's, Thelonious Monk’s, Sonny Rollins', Benny Goodman's, Lee Konitz's, and Tony Scott's. He can be spotted holding down the low-end in the popular documentary made about that year’s festival, Jazz on a Summer’s Day. That same year he even got to play some gigs with Miles Davis' group featuring John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderly, Bill Evans, and Philly Joe Jones—the most prominent small group in jazz at the time—when regular bassist Paul Chambers wasn’t available.

This earliest part of Grimes’s career is not well represented in the Jazz Music Library, with the exception being a couple boyantly swinging albums under the leadership of pianist Billy Taylor, Uptown (1960) and Warming Up (1960). He also appears on a few cuts from The Best of Chet Baker with the Gerry Mulligan Quartet.

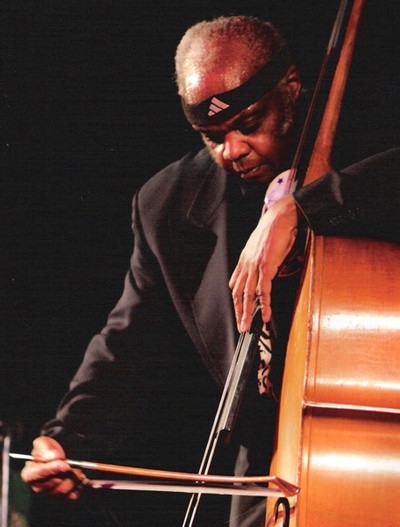

As the 1960s took form as the most radical decade in music history, Grimes was working in ever more experimental settings. The earliest is the post-bop classic Out of the Afternoon (1962), led by drummer Roy Haynes. The album opens with a cymbal flourish and Grimes' richly bowed bass, summoning the quartet's off-kilter swing with a dramatic fanfare. Researching for this essay, your humble librarian-blogger learned that the track "Snap Crackle" was used in the game Grand Theft Auto IV, suggesting a whole cohort of listeners who may have enjoyed Grimes' art unawares. The next year, Grimes and Haynes supplied the rhythm section on Reaching Fourth (1963) by West Philadelphia native McCoy Tyner, best known as the piano player for Philadelphian John Coltrane, the subject of the first Philly Jazz Legends post. On the title track, Grimes plays a lovely nimble solo, again with his bow rather than playing pizzicato (i.e. using the fingers of the right hand) as is more common with jazz bass solos.

By the mid-1960s, Grimes became involved in the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, playing many fundraising concerts at Harlem’s Center for African Culture. Out of this foment came such albums as On This Night (1965), led by Germantown native Archie Shepp (the subject of a previous Philly Jazz Legends post too). Check out how deftly Grimes realizes Shepp’s radical vision on "The Pickaninny," playing with a tough lurching swing but pivoting on a dime towards tender asides.

Astonishingly flexible, Grimes was able to work with some of the era’s most groundbreaking musical thinkers in the coming years. Pianist Cecil Taylor, also conservatory trained, employed him on his head-scratching and paradigm-shifting 1966 masterworks Unit Structures and Conquistador! Trumpeter Don Cherry used him on the joyfully polyphonic Where is Brooklyn? (1966). He joined the ecstatic sound world of saxophonist Albert Ayler on Live in Greenwich Village (1967), and he held down the low end on Tauhid (1967) by Pharaoh Sanders, the godfather of "spiritual jazz." Someone curious about the experimental jazz of the mid-to-late-1960s would, after checking out each of these records, have a strong sense of both the depth of the experiments and the wide variety of their outcomes—making it all the more astonishing that Grimes could play on all of them.

Grimes, the consummate sideman, had precisely one date as a bandleader during this era, out of which came the trio album The Call. It’s not on the Jazz Music Library, but given its significance to Grimes’s discography, it’s worth pointing out that it can be streamed free on Bandcamp. Anyone suspecting that avant-garde jazz is by definition harsh or dour would do well to check out the delightful ditty "Son of Alfalfa," taking note of how playfully Grimes deconstructs the melody on his bass solo.

Late in 1967, a West Coast tour went awry, resulting in Grimes needing to sell his damaged bass and stay in Los Angeles. This coincided with the sharp decline in the popularity of forward-thinking jazz—never a very profitable endeavor in the first place—which was displaced by adventurous rock as the music of choice for "turned on" youth. Grimes had always been a quiet soul, and he quickly dropped out of touch with his old musical comrades, to the point where he was widely assumed to have died at some point in the 1970s.

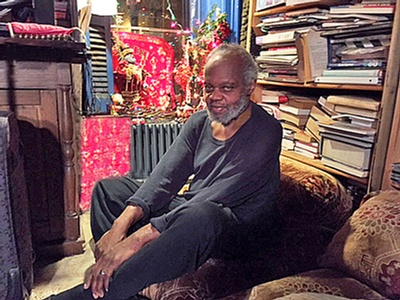

Then more than thirty years later came one of the greatest rediscovery stories in American music since Mississippi John Hurt. In 2002, a social worker and jazz fan from Georgia decided to seek out Grimes' final resting place and, to his astonishment, he found the man himself living in a shelter in downtown LA. In the intervening decades, Grimes had dealt with addiction, lived on the street at times, picked up janitorial and construction work here and there, wrote reams of poetry, and somehow assumed that the groundbreaking music to which he’d been central had been forgotten—to the extent that his "redicoverers" reportedly had to explain to him what a CD was.

Once the word was out, there was a groundswell of support in the jazz community to get Grimes playing again. The bassist William Parker gave him an instrument, and after a few months of practice and some smaller performances in LA, he made his triumphant homecoming to New York City at Parker’s vital Vision Festival in 2003. For the next decade and a half, he was just as prolific as in his heyday, touring the world constantly, playing on almost a hundred recordings, teaching masterclasses, and even making his professional debut on a new instrument (the violin) alongside Cecil Taylor at Lincoln Center in New York. This period is also not well represented on the Jazz Music Library, which in general much better captures the jazz of the 1920s to the 1960s. The one exception is a searching solo album, Henry Grimes Solo, from 2009.

Grimes’s major legacy, however, was as one of the great accompanists in jazz history, able to take someone else's ensemble and tune and support it perfectly or complicate it artfully, as the circumstance called for. So it's best to end with one of the most celebrated groups of his later life: the band that guitarist Marc Ribot first put together to pay tribute to the music of Albert Ayler, which also features Philadelphia transplant Chad Taylor (who readers may have caught at the Free Library’s Mysterious Travellers series a few years back). "Invocation" opens with a blunt bowed bass figure that invokes the raw spirit of Ayler, Grimes’s former musical accomplice, who died under unknown circumstances in 1970. Henry Grimes, who the world thought had met a similar fate, finally passed away from complications of Parkinson's disease and COVID-19 on April 15, 2020.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.