Despite giving us the straightforward phrase “the law of the land,” medieval laws were overlapping and complex.

Whether you live in Philadelphia or in Delaware County, you’re expected to follow laws passed locally as well as state and federal laws. The medieval period also had intersecting laws, including religious laws that people would be expected to follow even if they were not members of that religion. Laws controlled where people could live and the jobs they could take; laws also directed who could change laws. And laws did change over time. For example, English kings passed statutes regularly, which were arranged into collections (the so-called Old Statutes, dating from 1215, were followed by the New Statutes, beginning with the reign of King Edward III in 1327).

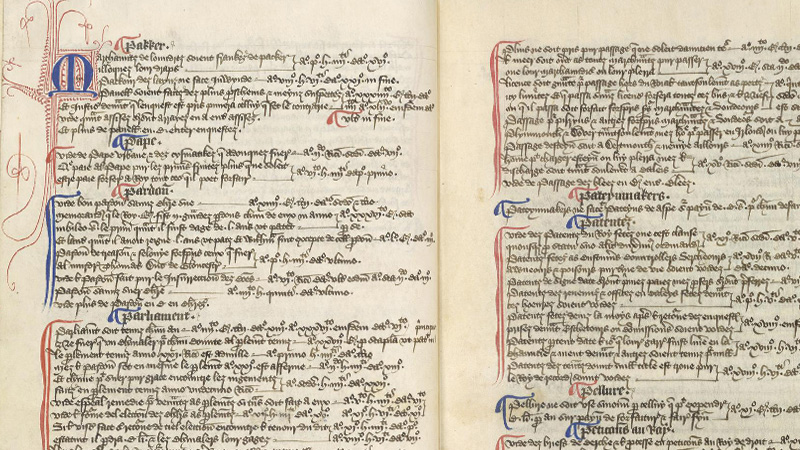

Statuta nova

England, circa 1488

This law book is written in both Anglo-Norman and Latin. It includes statutes from the time of King Edward III, who ruled from 1327 to 1377, through 1488, during the reign of King Henry VII. On view here is the index, which appears at the beginning of the book.

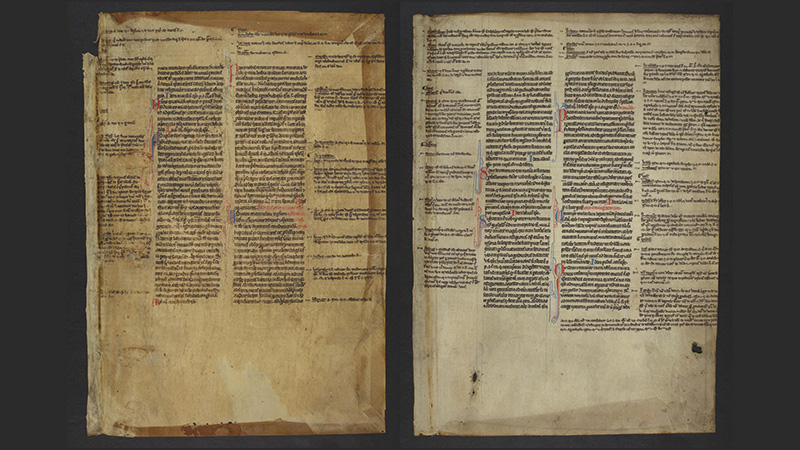

Statuta vetera

England, circa 1301

Here is another miniature law book, open to the end of the Magna Carta (on the left you may be able to read the words "Explicit magna carta") and the beginning of the Carta de Foresta. The Magna Carta is the rights document first issued in 1215 that became the basis for English common law, the British Parliament, and the United States’ Bill of Rights. The Carta de Foresta is something of a complement to the Magna Carta, reestablishing peasants’ access to the royal forest, which had been limited for nearly 200 years after William the Conqueror and the Norman invasion of England.

Tractatus de maleficiis

This treatise on criminal law, the Treatise on Evil Deeds, is by the 15th-century judge Angelo de Gambiglioni. This particular copy is unusual: it includes drawings in the border—like these sword-fighting doodles—that illustrate a number of the crimes discussed within.

Manuscript leaves from a canon law text

Germany, mid-13th century

These two pages are from an important book of law for the Catholic Church, the Decretals of Gregory IX. They were cut from a copy made in the mid-13th century and used in the binding of a book in the 1500s, which explains the glue marks and discoloration, particularly around the edges.

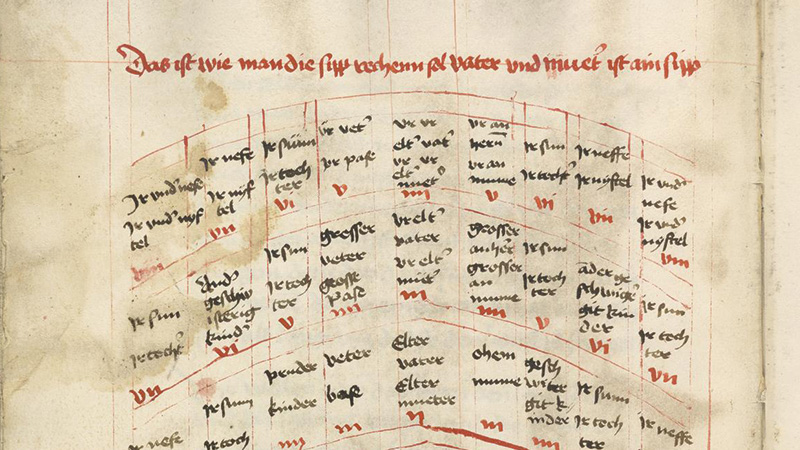

Chart of consanguinity

Bavaria (?), Germany, circa 1350–1400

A chart of consanguinity outlines kinship relationships from one degree of separation to the next. At one degree of separation is a person’s closest relatives: their children or their parents. Each additional degree extends the blood relationship (at four degrees are great-great grandparents and first cousins, for example). Both church and civil law had rules about how close was too close for marriage.