Item Info

Media Type: House Organs

Source: Theatre Collection

Notes:

Lubin’s Famous Players: Joseph W. Smiley.

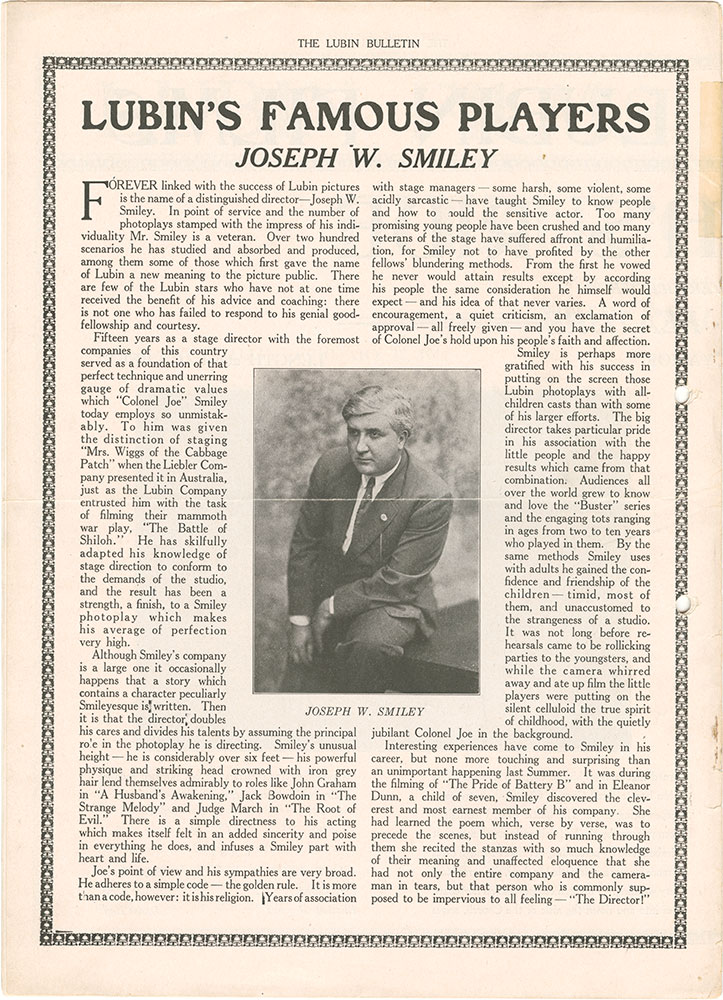

Forever linked with the success of Lubin pictures is the name of a distinguished director — Joseph W. Smiley. In point of service and the number of photoplays stamped with the impress of his individuality Mr. Smiley is a veteran. Over two hundred scenarios he has studied and absorbed and produced, among them some of those which first gave the name of Lubin a new meaning to the picture public. There are few of the Lubin stars who have not at one time received the benefit of his advice and coaching: there is not one who has failed to respond to his genial goodfellowship and courtesy.

Fifteen years as a stage director with the foremost companies of this country served as a foundation of that perfect technique and unerring gauge of dramatic values which “Colonel Joe” Smiley today employs so unmistakably. To him was given the distinction of staging “Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch” when the Liebler Company presented it in Australia, just as the Lubin Company entrusted him with the task of filming their mammoth war play, “The Battle of Shiloh.” He has skillfully adapted his knowledge of stage direction to conform to the demands of the studio, and the result has been a strength, a finish, to a Smiley photoplay which makes his average of perfection very high.

Although Smiley’s company is a large one it occasionally happens that a story which contains a character peculiarly Smileyesque is written. Then it is that the director doubles his cares and divides his talents by assuming the principal role in the photoplay he is directing. Smiley’s unusual height — he is considerably over six feet — his powerful physique and striking head crowned with iron grey hair lend themselves admirably to roles like John Graham in “A Husband’s Awakening,” Jack Bowdoin in “The Strange Melody” and Judge March in “The Root of Evil.” There is a simple directness to his acting which makes itself felt in an added sincerity and poise in everything he does, and infuses a Smiley part with heart and life.

Joe’s point of view and his sympathies are very broad. He adheres to a simple code — the golden rule. It is more than a code, however: it is his religion. Years of association with stage managers — some harsh, some violent, some acidly sarcastic — have taught Smiley to know people and how to should the sensitive actor. Too many promising young people have been crushed and too many veterans of the stage have suffered affront and humiliation, for Smiley not to have profited by the other fellows’ blundering methods. From the first he vowed he never would attain results except by according his people the same consideration he himself would expect — and his idea of that never varies. A word of encouragement, a quiet criticism, an exclamation of approval — all freely given — and you have the secret of Colonel Joe’s hold upon his people’s faith and affection.

Smiley is perhaps more gratified with his success in putting on the screen those Lubin photoplays with all children casts than with some of his larger efforts. The big director takes particular pride in his association with the little people and the happy results which came from that combination. Audiences all over the world grew to know and love the “Buster” series and the engaging tots ranging in ages from two to ten years who played in them. By the same methods Smiley uses with adults he gained the confidence and friendship of the children — timid, most of them, and unaccustomed to the strangeness of a studio. It was not long before rehearsals came to be rollicking parties to the youngsters, and while the cameras whirred away and ate up film the little players were putting on the silent celluloid the true spirit of childhood, with the quietly jubilant Colonel Joe in the background.

Interesting experiences have come to Smiley in his career, but non more touching and surprising than an unimportant happening last Summer. It was during the filming of “The Pride of Battery B” and in Eleanor Dunn, a child of seven, Smiley discovered the cleverest and most earnest member of his company. She had learned the poem which, verse by verse, was to precede the scenes, but instead of running through them she recited the stanzas with so much knowledge of their meaning and unaffected eloquence that she had not only the entire company and the cameraman in tears, but that person who is commonly supposed to be impervious to all feeling — “The Director!”

Call Number: Lubin - Bulletin I:8

Front Cover (Page 1)

Front Cover (Page 1)  Her Wayward Son (Page 2)

Her Wayward Son (Page 2)  The Catch of the Season (Page 3)

The Catch of the Season (Page 3)  The Vagaries of Fate (Page 6)

The Vagaries of Fate (Page 6)  Pat's Revenge / Her Side-Show Sweetheart (Page 7)

Pat's Revenge / Her Side-Show Sweetheart (Page 7)  Taming Terrible Ted / Antidotes for Suicide (Page 8)

Taming Terrible Ted / Antidotes for Suicide (Page 8)  The Measure of a Man (Page 9)

The Measure of a Man (Page 9)  Lubin's Famous Players (Page 12 - Back Cover)

Lubin's Famous Players (Page 12 - Back Cover)