Item Info

Media Type: House Organs

Source: Theatre Collection

Notes:

Lubin’s Famous Players: Romaine Fielding.

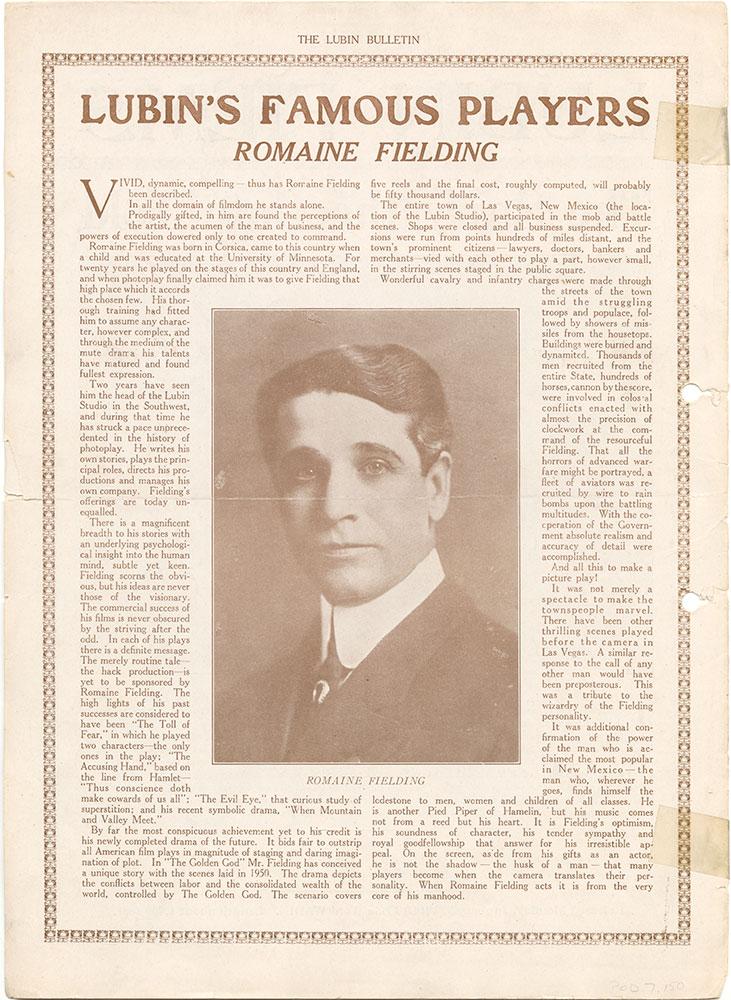

Vivid, dynamic, compelling — thus has Romaine Fielding been described.

In all the domain of filmdom he stands alone.

Prodigally gifted, in him are found the perceptions of the artist, the acumen of the man of business, and the powers of execution dowered only to one create to command.

Romaine Fielding was born in Corsica, came to this country when a child and was educated at the University of Minnesota. For twenty years he played on the stages of this country and England, and when photoplay finally claimed him it was to give Fielding that high place which it accords the chosen few. His thorough training had fitted him to assume any character, however complex, and through the medium of the mute drama his talents have matured and found fullest expression.

Two years have seen him the head of the Lubin Studio in the Southwest, and during that time he has struck a pace unprecedented in the history of photoplay. He writes his own stories, plays the principals roles, directs his productions and manages his own company. Fielding’s offerings are today unequalled.

There is a magnificent breadth to his stories with an underlying psychological insight into the human mind, subtle yet keen. Fielding scorns the obvious, but his ideas are never those of the visionary. The commercial success of his films is never obscured by the striving after the odd. In each of his plays there is a definite message. The merely routine tale — the hack production — is yet to be sponsored by Romaine Fielding. The high lights of his past success are considered to have been “The Toll of Fear,” in which he played two characters — the only ones in the play; “The Accusing Hand,” based on the line from Hamlet — “Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all”; “The Evil Eye,” that curious study of superstition; and his recent symbolic drama, “When Mountain and Valley Meet.”

By far the most conspicuous achievement yet to his credit is his newly completed drama of the future. It bids fair to outstrip all American film plays in magnitude of staging and daring imagination of plot. In “The Golden God” Mr. Fielding has conceived a unique story with the scenes laid in 1950. The drama depicts the conflicts between labor and the consolidated wealth of the world, controlled by The Golden God. The scenario covers five reels and the final cost, roughly computed, will probably be fifty thousand dollars.

The entire town of Las Vegas, New Mexico (the location of the Lubin Studio), participated in the mob and battle scenes. Shops were closed and all business suspended. Excursions were run from points hundreds of miles distant, and the town’s prominent citizens — lawyers, doctors, bankers and merchants — vied with each other to play a part, however small, in the stirring scenes staged in the public square.

Wonderful cavalry and infantry charges were made through the streets of the town amid the struggling troops and populace, followed by showers of missiles from the housetops. Buildings were burned and dynamited. Thousands of men recruited from the entire State, hundreds of horses, cannon by the score, were involved in colossal conflicts enacted with almost the precision of clockwork at the command of the resourceful Fielding. That all the horrors of advanced warfare might be portrayed, a fleet of aviators was recruited by wire to rain bombs upon the battling multitudes. With the cooperation of the Government absolute realism and accuracy of detail were accomplished.

And all this to make a picture play!

It was not merely a spectacle to make the townspeople marvel. There have been other thrilling scenes played before the camera in Las Vegas. A similar response to the call of any other man would have been preposterous. This was a tribute to the wizardry of the Fielding personality.

It was additional confirmation of the power of the man who is acclaimed the most popular in New Mexico — the man who, wherever he goes, finds himself the lodestone to men, women and children of all classes. He is another Pied Piper of Hamelin, but his music comes not from a reed but his heart. It is Fielding’s optimism, his soundness of character, his tender sympathy and royal goodfellowship that answer for his irresistible appeal. On the screen, aside from his gifts as an actor, he is not the shadow — the husk of a man — that many players become when the camera translates their personality. When Romaine Fielding acts it is from the very core of his manhood.

Call Number: Lubin - Bulletin I:5

Front Cover (Page 1)

Front Cover (Page 1)  Her Boy (Page 2)

Her Boy (Page 2)  Before the Last Leaves Fall (Page 3)

Before the Last Leaves Fall (Page 3)  The Death Trap (Page 4)

The Death Trap (Page 4)  The Doctor's Romance (Page 5)

The Doctor's Romance (Page 5)  The Parasite (Page 6 and 7)

The Parasite (Page 6 and 7)  The Inspector's Story (Page 8)

The Inspector's Story (Page 8)  A Corner In Popularity / The Missing Diamond (Page 9)

A Corner In Popularity / The Missing Diamond (Page 9)  The Circle's End (Page 10)

The Circle's End (Page 10)  The Story the Gate Told (Page 11)

The Story the Gate Told (Page 11)  Lubin's Famous Players (Page 12 - Back Cover)

Lubin's Famous Players (Page 12 - Back Cover)