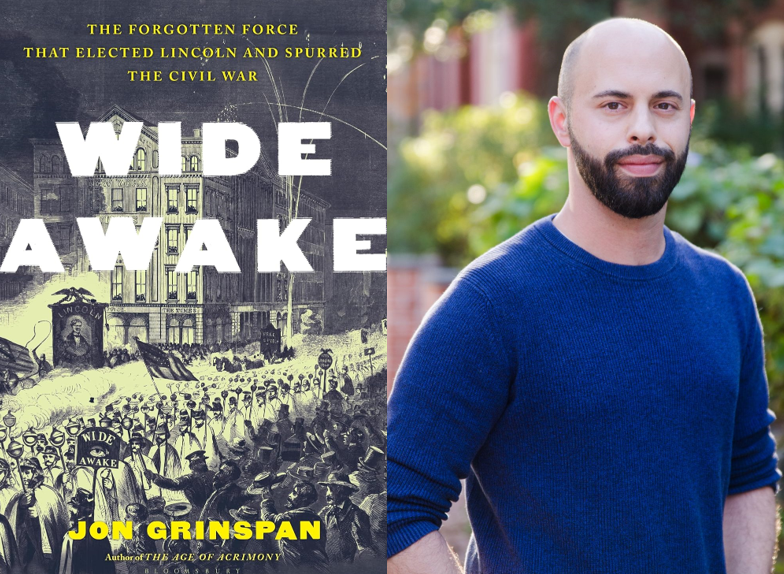

On Thursday, October 10, in the Fourth Floor Skyline Room at Parkway Central Library, the Social Science and History Department will host Jon Grinspan, curator of political history at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

Grinspan will be in Philadelphia to discuss his latest book, Wide Awake: The Forgotten Force that Elected Lincoln and Spurred the Civil War, a propulsive account of one of U.S. history's most consequential political clubs: the Wide Awake anti-slavery youth movement that marched America from the 1860 election to the Civil War. Grinspan is a frequent contributor to the New York Times, and in his most recent essay there is an abbreviated version of the book, concluding,

"Textbooks use the passive phrase, 'The Coming of the Civil War.' But the war didn’t come. Americans brought it, argued it, protested it into being. The Wide Awakes help re-politicize that story, as an unfolding and uncertain tug of war between speech and action, equal parts inspiring and troubling. Marching for the best of causes, they helped bring on the worst of consequences."

Registration for the talk is encouraged but not required. Whether you can make it to the talk or not, check out these books from our collection about the complex causes of the Civil War.

The Causes of the U.S. Civil War

This book tells the story of America's original sin — slavery — through politics, law, literature, and above all, through the eyes of enslaved Black people who risked their lives to flee from bondage, thereby forcing the nation to confront the truth about itself. The struggle over slavery divided not only the American nation but also the hearts and minds of individual citizens faced with the timeless problem of when to submit to unjust laws and when to resist. The War Before the War illuminates what brought us to war with ourselves and the terrible legacies of slavery that are with us still.

The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom

What do moral people do when democracy countenances evil? The question, implicit in the idea that people can govern themselves, came to a head in America in the middle of the 19th century, in the struggle over slavery. John Brown's answer was violence — violence of a sort some in later generations would call terrorism. Brown was a deeply religious man who heard the God of the Old Testament speaking to him, telling him to do whatever was necessary to destroy slavery. When Congress opened Kansas territory to slavery, the eerily charismatic Brown raised a band of followers to wage war against the evil institution. One dark night his men tore several proslavery settlers from their homes and hacked them to death with broadswords, as a bloody warning to others. Three years later Brown and his men assaulted the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, to furnish slaves with weapons to murder their masters in a race war that would cleanse the nation of slavery once and for all. Abraham Lincoln's answer was politics. Lincoln was an ambitious lawyer and former office-holder who read the Bible not for moral guidance but as a writer's primer. He disliked slavery yet didn't consider it worth shedding blood over. He distanced himself from John Brown and joined the moderate wing of the new, antislavery Republican party. He spoke cautiously and dreamed big, plotting his path to Washington and perhaps the White House. Yet Lincoln's caution couldn't preserve him from the vortex of violence Brown set in motion. Arrested and sentenced to death, Brown comported himself with such conviction and dignity on the way to the gallows that he was canonized in the North as a martyr to liberty. Southerners responded in anger and horror that a terrorist was made into a saint. Lincoln shrewdly threaded the needle of the fracturing country and won the election as president, still preaching moderation. But the time for moderation passed. Slaveholders lumped Lincoln with Brown as an enemy of the Southern way of life; seven Southern states left the Union. Lincoln resisted secession, and the Civil War followed. At first a war for the Union became the war against slavery Brown had attempted to start. Before it was over, slavery had been destroyed, but so had Lincoln's faith that democracy could resolve its moral crises peacefully.

The Stormy Present: Conservatism and the Problem of Slavery in Northern Politics, 1846-1865

In this engaging and nuanced political history of Northern communities in the Civil War era, Adam I. P. Smith offers a new interpretation of the familiar story of the path to war and ultimate victory. Smith looks beyond the political divisions between abolitionist Republicans and Copperhead Democrats to consider the everyday conservatism that characterized the majority of Northern voters. A sense of ongoing crisis in these Northern states created anxiety and instability, which manifested in a range of social and political tensions in individual communities. In the face of such realities, Smith argues that a conservative impulse was more than just a historical or nostalgic tendency; it was fundamental to charting a path to the future. At stake for Northerners was their conception of the Union as the vanguard in a global struggle between democracy and despotism, and their ability to navigate their freedoms through the stormy waters of modernity. As a result, the language of conservatism was peculiarly, and revealingly, prominent in Northern politics during these years. The story this book tells is of conservative people coming, in the end, to accept radical change.

Fanatics and Fire-Eaters: Newspapers and the Coming of the Civil War

In the troubled years leading up to the Civil War, newspapers in the North and South presented the arguments for and against slavery, debated the right to secede, and in general denounced opposing viewpoints with imagination and vigor. At the same time, new technologies like railroads and the telegraph lent the debates an immediacy that both enflamed emotions and brought the slavery issue into every home.

Lorman A. Ratner and Dwight L. Teeter Jr. look at the power of America's fast-growing media to influence perception and the course of events before the Civil War. Drawing on newspaper accounts from across the United States, the authors look at how the media covered — and the public reacted to — major events like the Dred Scott decision, John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry, and the election of 1860. They find not only North-South disputes about the institution of slavery but differing visions of the republic itself — and which region was the true heir to the legacy of the American Revolution.

Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789-1859

In the decades of the early republic, Americans debating the fate of slavery often invoked the specter of disunion to frighten their opponents. As Elizabeth Varon shows, "disunion" connoted the dissolution of the republic — the failure of the founders' effort to establish a stable and lasting representative government. For many Americans in both the North and the South, disunion was a nightmare, a cataclysm that would plunge the nation into the kind of fear and misery that seemed to pervade the rest of the world. For many others, however, disunion was seen as the main instrument by which they could achieve their partisan and sectional goals. Varon blends political history with intellectual, cultural, and gender history to examine the ongoing debates over disunion that long preceded the secession crisis of 1860-61.

Half-Slave and Half-Free: The Roots of the Civil War

In a revised edition, brought completely up to date with a new preface and afterword and an expanded bibliography, Bruce Levine's succinct and persuasive treatment of the basic issues that precipitated the Civil War is as compelling as ever. Levine explores the far-reaching, divisive changes in American life that came with the incomplete Revolution of 1776 and the development of two distinct social systems, one based on slavery, the other on free labor — changes out of which the Civil War developed.

The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War

When gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in 1848, Americans of all stripes saw the potential for both wealth and power. Among the more calculating were Southern slave owners. By making California a slave state, they could increase the value of their slaves — by 50 percent at least, and maybe much more. They could also gain additional influence in Congress and expand Southern economic clout, abetted by a new transcontinental railroad that would run through the South. Yet, despite their machinations, California entered the union as a free state. Disillusioned Southerners would agitate for even more slave territory, leading to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and, ultimately, to the Civil War itself.

The Approaching Fury: Voices of the Storm, 1820-1861

An award-winning historian tells the story of the approach of the Civil War through the voices of 13 principal figures, from Abraham Lincoln to Frederick Douglass, exploring the different perceptions they had of the reasons for war.

The Scorpion's Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War

This book explores the Civil War and the anti-slavery movement, specifically highlighting the plan to help abolish slavery by surrounding the slave states with territories of freedom and discussing the possibility of what could have been a more peaceful alternative to the war.

At the end of the 18th century, a massive slave revolt rocked French Saint Domingue, the most profitable European colony in the Americas. Under the leadership of the charismatic former slave François Dominique Toussaint Louverture, a disciplined and determined republican army, consisting almost entirely of rebel slaves, defeated all of its rivals and restored peace to the embattled territory. The slave uprising that we now refer to as the Haitian Revolution concluded on January 1, 1804, with the establishment of Haiti, the first "Black republic" in the Western Hemisphere.

The Haitian Revolution cast a long shadow over the Atlantic world. In the United States, according to Matthew J. Clavin, there emerged two competing narratives that vied for the revolution's legacy. One emphasized vengeful African slaves committing unspeakable acts of violence against white men, women, and children. The other was the story of an enslaved people who, under the leadership of Louverture, vanquished their oppressors to eradicate slavery and build a new nation.

Toussaint Louverture and the American Civil War examines the significance of these competing narratives in American society on the eve of and during the Civil War. Clavin argues that at the height of the longstanding conflict between North and South, Louverture and the Haitian Revolution were resonant, polarizing symbols, which antislavery and proslavery groups exploited both to provoke a violent confrontation and to determine the fate of slavery in the United States. In public orations and printed texts, African Americans and their white allies insisted that the Civil War was a second Haitian Revolution, a bloody conflict in which thousands of armed bondmen, "American Toussaints," would redeem the republic by securing the abolition of slavery and proving the equality of the Black race. Southern secessionists and northern anti-abolitionists responded by launching a cultural counterrevolution to prevent a second Haitian Revolution from taking place.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.