George Orwell, who was born on this day 115 years ago, entered the world as Eric Arthur Blair. It is fitting that this legend of dystopian literature—which essentially puts a mask on ills within our current society—also wore a personal mask, creating a persona that lives on today. And which seems to have taken on ever-greater resonance in our current political landscape.

His pen name has long been an adjective unto itself—"Orwellian"—describing conditions counter to free and open society. Use of the word has spiked in recent years, more so in recent months (although it is sometimes used inaccurately, for dramatic effect, to refer to any political idea someone does not like). So too have other phrases he coined, like "Big Brother" and "Room 101", become common references. Just as he invented a name to represent his more politically rebellious self, he invented terminology to refer to politically insidious ideas—masked as simple, possibly even friendly notions. (Brothers are good, aren’t they?)

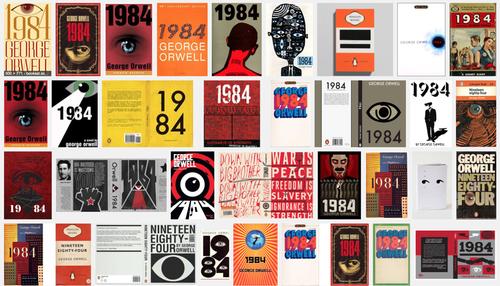

His seminal work, 1984, is also in the midst of a renaissance, having recently hit the bestseller list again—nearly 70 years after its initial publication. Along with renewed Orwell interest, it is part of a larger trend of high interest in literary dystopias in general. The trend was chronicled last year in the New Yorker’s feature “A Golden Age for Dystopian Fiction: What to Make of Our New Literature of Radical Pessimism.”

What is the ever-growing power of this genre?

In 1984,

Perhaps these works serve as a balm for growing anxieties about an audience’s present. Perhaps they are also a powerful thought experiment—the closest we can get to a futuristic science experiment—and a what-if that also, often, serves as a warning. The New Yorker piece posited that “the argument of dystopianism is that perfection comes at the cost of freedom.”

Do to otherwise would be doubleplusungood. Happy birthday, George Orwell.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.