A History Minute: 11 Things You Should Know About the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918

By Sally F.As we enter into the yearly flu season here in the United States, it was 100 years ago that Philadelphia itself was the epicenter of a world health pandemic. Young people in the prime of their lives died in horrifying ways and there was no cure, no preventative. It was one of the darkest chapters in our history.

Here are 11 Things You Should Know About the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918:

- The Spanish Flu was the worst pandemic the world has ever known.

One-fifth of the world’s population contracted the disease. Between 50 and 100 million people died. In the U.S. the flu claimed the lives of over 670,000: more than all the wars of the 20th century combined.

- Philadelphia was the hardest hit city in the U.S.

At the epidemic’s peak in October, 1918, more people died here than anywhere else in the country. One-third of Philadelphia’s population contracted the flu and 13,000 lost their lives. Most of this happened during the course of one month.

At the epidemic’s peak in October, 1918, more people died here than anywhere else in the country. One-third of Philadelphia’s population contracted the flu and 13,000 lost their lives. Most of this happened during the course of one month.

- The epidemic arrived at Philadelphia Navy Yard in September.

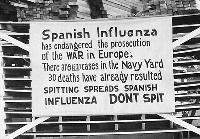

With 300 sailors shipped from Boston, several were ill and within a few days the naval hospital was overwhelmed with sick sailors who were then sent to Pennsylvania Hospital. Two days later doctors and nurses there began to collapse with flu symptoms. Local newspapers had been reporting on the epidemic in Boston and Fort Dix for weeks, but insisted that it was contained at the Navy Yard. Philadelphia’s health officials did nothing. This head-in-the-sand attitude may have been encouraged by the recently passed Sedition Act. Government posters asked people to report anyone “who spreads pessimistic stories…” that might encourage the enemy.

With 300 sailors shipped from Boston, several were ill and within a few days the naval hospital was overwhelmed with sick sailors who were then sent to Pennsylvania Hospital. Two days later doctors and nurses there began to collapse with flu symptoms. Local newspapers had been reporting on the epidemic in Boston and Fort Dix for weeks, but insisted that it was contained at the Navy Yard. Philadelphia’s health officials did nothing. This head-in-the-sand attitude may have been encouraged by the recently passed Sedition Act. Government posters asked people to report anyone “who spreads pessimistic stories…” that might encourage the enemy.

- No one wanted to discourage the Liberty Loan parade.

It would be the greatest parade in Philadelphia history, stretching over two miles. It would prove Philadelphia’s patriotism. Over 200,000 people marched in or attended the parade, including many of sailors and soldiers from the base. It was a huge success, raising over $600 million in war bonds. It was even more successful in spreading the flu. Three days later 635 new cases were reported. Every bed in 31 hospitals was filled.

- Philadelphia was not prepared to fight an epidemic.

At least half of the city’s doctors, nurses and other medical personnel were serving at the front. Several hundred thousand workers had come to the city to work in the shipyards and munitions factories feeding the war effort. These workers were squeezed into what were already the nation’s most crowded slums. The city was run by the Republican politcal machine that used public funds to line their pockets and buy votes, rather than build sewers and clean streets. The politically appointed Director of Public Health, Wilmer Krusen, insisted this was just a seasonal flu and nothing to worry about. The mayor was no help, as he was in jail on corruption charges!

- In the absence of city services, Philadelphia’s prominent families stepped in.

Led by George Wharton Pepper, they commandeered public school kitchens to prepare food for the sick who could not feed themselves and organized volunteers to deliver it. They paid people to collect and bury the dead and brought in embalming students from outlying areas. Strawbridge and Clothier donated phone lines for information on where to get help. The Catholic Archdiocese sent nuns to hospitals as nurses, priests and seminary students to homes to collect bodies and used city steam shovels to dig trenches for graves. Hundreds volunteered to transport doctors and used their cars as ambulances. Philadelphia’s medical schools sent 300 fourth-year students to assist doctors in makeshift hospitals throughout the city and the pharmacy schools sent students to assist pharmacists.

- Unlike other flus, this one killed those between age 20 and 45.

Pregnant women and newborns were the most vulnerable. The gauze masks everyone wore were no protection. The virus was far smaller than the pores of the fabric, too small to be seen under microscopes until 1933. Hundreds died every day, far more than could be buried. The death rate in a week was 700 times higher than usual. And these were horrifying deaths. Many victims seemed to get better only to suddenly turn black and die vomiting blood. The life of the city ground to a halt. Men and women in the prime of life were decimated, leaving children without parents and businesses without workers. People could not buy food or heating oil. Trains and trolleys were few and far between and cars disappeared from the roads.

-

By mid-October the death toll had peaked and fewer cases were being reported.

By the end of the month, schools and businesses had opened and life began to return to normal. On November 11, Philadelphians gathered for another parade to celebrate the end of WWI. Flu cases spiked again after the parade, but these were milder, more like the usual seasonal flu. Those left in the city had developed some immunity.

-

The Spanish flu wasn’t Spanish.

When the epidemic first made itself known, Europe was embroiled in World War I. Huge armies were huddled into trenches or in crowded camps behind the lines, prime conditions for the spread of an airborne virus. Thousands became ill and incapacitated. But it’s hard to strike fear into the hearts of your enemies when your soldiers are sick in bed. The powers on both sides kept news of the flu out of their newspapers, which were censored during wartime. Neutral Spain, with its uncensored newspapers, reported freely on the epidemic and appeared to be the first to suffer from it. Other nations were glad to point the finger at Spain as the source of the epidemic. Where did it come from? Researchers have been trying to figure that out for the last 100 years. They have narrowed it down to 3 locations: Haskell County, Kansas, Etaples, France, and Shanxi, China.

-

The 1918 Flu led to the development of the flu vaccines we benefit from today.

On Oct. 19, 1918 Dr. C.Y. White delivered 10,000 doses of his vaccine to the Philadelphia Health Department. He was one of many throughout the world who attempted to prevent the flu with a vaccine based on bacteria found in the lungs. None of these vaccines were effective against the flu, which is a viral disease, but fears of another pandemic stimulated research. Jonas Salk and Thomas Francis developed the first effective flu vaccine in 1938, just in time to protect the soldiers who would fight in World War II. While today’s flu vaccines do not give 100% protection from the flu they offer significant protection from serious complications and death.

-

Viral descendants of the 2018 flu caused epidemics in 1957, 1968, and 2009.

We know this because researchers have isolated genetic material from autopsy slides and bodies exhumed from Alaskan permafrost and compared it to tissue samples from later pandemics.

Additional Resources

Listen:

"I Remember When: What Became of the Influenza Pandemic of 1918."

Read:

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.