#OneBookWednesday: Brooklyn, Black Girlhood, and the Great Migration

By AdministratorGladys Jamison couldn’t know this, but she was a girl coming of age in an exodus. Thirteen years old when her father moved her and her siblings to Brooklyn, she’d lost her mother five years before, in 1932. She was still reeling from her death.

The daughter of farmers, Gladys grew up in Bowman, South Carolina, the nexus of a failed railroad line. Her parents were fortunate to own their land, but racism was a way of life. In town, there were public bathrooms Gladys could not use, fountains she could not drink from, waiting rooms she could not sit in. There was a school with freshly painted walls and new books on its shelves that she could not attend.

Brooklyn in the late 1930s was a world of newness for her. Concrete sidewalks replaced the silty soil that would have floured her knees as she played on her family’s land. Gladys might have missed the steady clop-clop-clop of mule drawn wagons along rutted dirt roads, instead hearing the sputters and coughs of automobiles, the scrapes and squeals of subway cars. Rigid factory schedules replaced the gradual shift of the sun in measuring a day’s work. Blistering cold swept over memories of mild and easy winters.

But she knew it was for a larger good. Never a warm nor loving man, Gladys’ father Eugene was strict and unbending, but he’d relocated his family in hopes of doing right by them—or at least, doing the best he could.

In the 1930s, he was one of thousands. From the start of World War I into the early 1970s, six million blacks climbed into wagons, boarded trains or piled into automobiles, exiting the American South in a movement now known as the Great Migration. Families left towns and farms, moving into cities—Chicago, San Francisco, New York, and Philadelphia—beginning with black men, first seeking factory jobs left by war-bound whites, and women scrabbling for domestic work. They were both emigrants and refugees—families like Eugene Jamison’s, chasing opportunity and fleeing the Jim Crow South.

But black Southerners did not find dreams waiting for them. They often found poverty. The jobs they were promised, if they panned out, were low-paying, yet demanded long hours and arduous, often dangerous work. They found discrimination. Legal or defacto segregation was often the case, and policies like redlining made it almost impossible for blacks to build wealth. Sometimes they found violence. Always, they found courage.

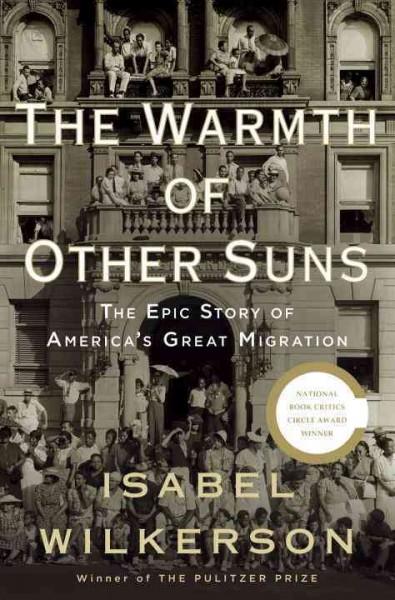

The best place to learn about this era is The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson, a compelling, comprehensive history. Another wonderful resource is The Great Migration: A City Transformed, an online project featuring audio-recorded firsthand stories of those who left the South to set down roots in Philadelphia. There is also a map showing what were once key Philadelphia sites for blacks who were part of the Great Migration. I retraced some of these Southerners’ steps, sharing them in a video.

But I choose to speak with Gladys and share her story, because her past dovetails with Jacqueline Woodson’s beautifully-wrought novel, Another Brooklyn. In Woodson’s work of fiction, a young girl is separated from her mentally-unstable mother when her family moves from Tennessee to Brooklyn, New York. Her father, while he works to make ends meet and seeks his own sense of community, also converts to Islam. The novel's protagonist isn’t sure where her faith stands. Her identity is wrapped in her friendship with three other girls as childhood fades into adulthood in the early 1970s.

In the novel, poetically rendered in the voice of character August, as well as in Gladys’ true-life story, told to me in a molasses-sweet drawl, losing one’s mother becomes an impetus for a family to leave the South. And like August’s father, Eugene Jamison isn’t someone to turn to. These men work hard to support their families, yet grapple with deep flaws, their spirituality complicating their children’s lives. Instead, August and Gladys rely on friendships to navigate the change from a familiar small town into the brisk, impersonal landscape of New York City.

In both narratives, there is a sense of adolescents raising themselves. And isn’t that what makes a good coming of age story?

Gladys first attended PS 35, a junior high school. She was struck that it was unsegregated, and that she shared the same classrooms with children of Jewish, Italian, Irish, Hispanic, and Asian backgrounds. But most of her friends, like her best friend Zelma, were black. Mostly, their parents mostly struggled to make a living, though some, like Gladys’ friend Savilla, came from established backgrounds. Gladys remembers Savilla’s beautiful home in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Others were high-achieving. Gladys’ friend Shirley, the class valedictorian, would one day become the first African-American congresswoman, and the first black candidate in a major party’s presidential nomination.

When Gladys moved up to high school at PS 178, she found that most of her friends enjoyed more freedom than Gladys’ very devoutly religious, strict father allowed. Gladys was a strong believer in her Christian faith, but her father felt that any disobedience, such as breaking curfew, was a sin against God.

Still, she found diversions. She would rent a bicycle for ten cents an hour, pedaling around her Fulton Street neighborhood. She and her friend Hilda would each pay a dime for a double feature at the theater on Howard Avenue, catching early shows so that Gladys could make curfew at dusk.

She loved summer jaunts to Coney Island, where she got aboard the Ferris wheel and other spinning rides. She felt she never could have had experiences like this in segregated South Carolina. In her home state, ropes separated the “colored” strand of beachfront from whites-only sections. At Coney Island’s beach, rope lines only functioned as tethers for bathers to hang onto, a necessary thing. Gladys, like many other Southerners, couldn’t swim.

But the first time she ventured into the surf, grasping the coarse rope, she became bold, easing into deeper waters as the cold waves pulsed over her waist and shoulders. When a giant, man-high wave rolled towards her, she knew she was in over her head, literally. The wave swallowed her whole, followed by another, and another. Clenching the rope, she panicked, desperate for air, but more waves crashed over her head until she could no longer hold her breath. Her hands weakened on the rope. The waves finally smoothed, letting her breathe and pull herself to the shallows. I will never let this happen again, she decided. Exhausted, gasping, and spitting up foam, she staggered onto the beach and plucked her clothes from the sand.

Gladys’ friendships were a highlight of her girlhood, but they could not be enough. Her father drank. Heavily. One night, one of his friends supported Eugene Jamison up the steps, and after helping him into bed, he made advances at Gladys. She was able to push him out, but she was furious that her father, so severe with his children, could himself behave so recklessly, throwing her in harm’s way. I will never let this happen again, she decided, remembering her near-drowning. She hastily gathered some money and packed her suitcase, stepping out into the soft springtime night to hail a taxi. Finding a phone, she called her oldest brother Le Roy who lived in a small town an hour’s drive from Bowman. Then she boarded a train.

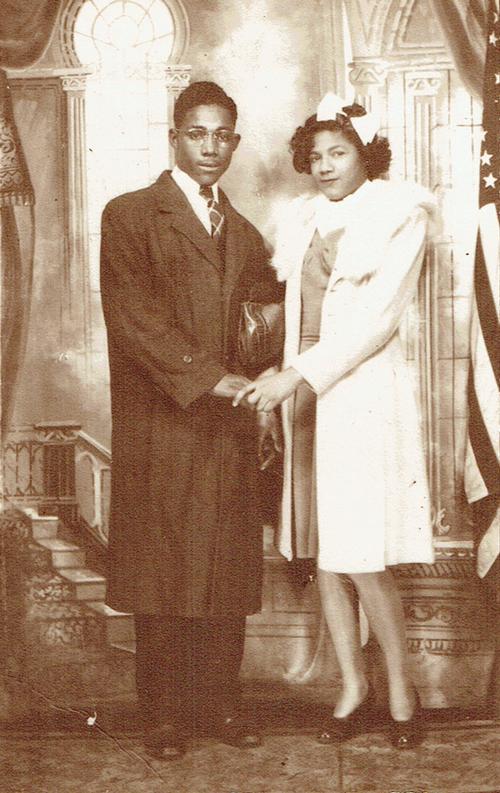

In South Carolina, Gladys enrolled in Alston High School and worked in Le Roy’s general store, but her mind was back in Brooklyn. Men from the nearby lumber mill flirted with her, calling her "the pretty girl from New York." But Gladys ignored them and instead considered the letter a former teacher sent. The teacher wanted Gladys to come back, promising to help her find a job. Perhaps Gladys was in the midst of making a decision when the bell above the door rang, signaling another customer. Jordan Simmons Jr. was the son of a brickmason. His family owned a stately home on land that had been theirs since Reconstruction.

The land off Pidgeon Bay Road in Summerville, South Carolina is still in that family. As a child, I played on that rambling acreage, my knees powdered with coarse, silty dirt. I’m part of the Simmons lineage. Living in another home on the property is my grandmother, Gladys Jamison Simmons Suddeth. She never made it back north, but her Brooklyn girlhood shaped her. She’s as sharp as flint and regrets nothing.

There must have been so many childhoods unfolding in the loam, in the dust, in the red clay Southern soils, the same earth bedding the roads which led away. There must have been thousands of young people like Gladys Jamison, who followed their families as they followed their hopes. Young people brimming with creativity, resilience, and curiosity, remaking the culture around them, as every African Diaspora has done from time immemorial.

I like to think of the Great Migration, an era fraught with turmoil and dizzying with anticipation, as America’s coming of age story. It shook loose what we’d always known. It raised us to be wise.

**Check back every #OneBookWednesday during the Reading Period for some more One Book food-for-thought!**

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.