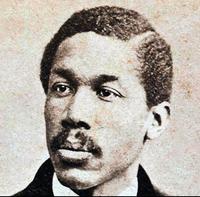

It has been more than 150 years since Octavius Catto may have slipped on a sack overcoat that hung by his front door, pushed a well-worn felt pocket hat over his parted hair, stepped out into the fall chill, and walked a few blocks down South Street to work, as horse-drawn traffic rattled past him. Born in 1839 in Charleston, South Carolina to free parents, Catto’s family moved to Philadelphia when he was a child. Though free from slavery, African Americans in Philadelphia endured segregation and second-class citizenship, which erected walls around what they could do and how they could make a living. This is the world Catto made his mark in.

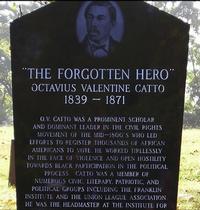

Octavius Catto was an activist, agitating for civil rights. He was an abolitionist, fighting for the emancipation of enslaved people in the South. He was a community leader, active in his church and in civic organizations. He was a friend, his circle of peers among Philadelphia’s black elite. He was a supporter of the Union Army, helping to raise United States Colored Troops regiments. He was an athlete, founding an African American baseball team. And he was a mentor who chose education as his livelihood, and saw it as his calling.

We have a brilliant biography of Catto in Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto in Civil War America by Daniel R. Biddle and Murray Dubin. And we can read a succinct, but comprehensive overview of his life in this previous post from last week. But where can we find traces of Octavius V. Catto in Philadelphia? How can we discover more about him? Can we walk where he once did? What is left to us and what has time taken?

We’ll start with what was once his home on the 800 block of South Street. The building is gone and South Street, with its eclectic and edgy vibe, has changed since its days as a utilitarian neighborhood. In the 1860s, there would have been narrow, low-slung row houses on this block, standing cheek-to-cheek with shops and hand-painted signs hung out front. Perhaps Catto may have started his morning with a stroll past 804 South Street, which was Ellis Peer’s Fine Cake Bakery. Ellis Peer, listed as 35 years old and "mulatto" in an 1860 census advertised in the Christian Recorder, an African American newspaper founded in the 19th century. So did Dr. Longfellow’s Surgeon Dentistry shop, nearby on 1126 Rodman Street, which promised "teeth plugged in the best of order." Mrs. Shorter Hawkins, who was likely Sarah S. Hawkins, a 38-year-old "mulatto" in the 1860 census, sold calicoes, flannels, muslins, and the all-important hoopskirts from 615 Lombard Street. Mrs. Henrietta Smith Bowers Duturte, following the death of her husband, took over his undertaking business on 634 Lombard Street. Business hummed along these corridors of Philadelphia. Catto likely waved to shopkeepers and neighbors as he passed by.

This was all part of Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward, a historically black community with its epicenter on South, Lombard, and Bainbridge Streets (then called Shippen), that reached as far north as Spruce Street and as far west as the Schuylkill River. This was an area with poverty, but also with commercial influence. White-owned businesses past the Seventh Ward vied for this community’s attention and its dollars, as evidenced by the Christian Recorder. George Katz on 503 Race Street’s Ice Cream and Confectionary Saloon sold "Water Ices of Superior Quality" (yes, even then Philly loved its water ice), and promised to have "Calves foot jelly always on hand” (Philly apparently loved that, too). Prussian-born August Tilmes—indeed, it was still Prussia then—was a confectioner on 1302 Chestnut Street. Finkle and Lyon sold the “best and cheapest" sewing machines from their store on 922 Chestnut Street.

Catto likely didn’t shop for sewing machines, but he probably frequented other shops in his neighborhood, and he almost certainly read the Christian Recorder. As recording secretary of the Banneker Institute, an African-American men’s literary society, he may have been the one responsible for sending the paper’s editors notes from the society’s yearly elections. He would have also noted about the numerous upcoming events in in his community. Many of the Seventh Ward’s churches, such as the famous Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, and Catto’s church, First African Presbyterian, where his father preached, opened their doors for concerts, social functions, and lecture series. Catto would have heard from notables, like Frederick Douglass—or people whose names our textbooks have failed to leave us. For instance, maybe Catto was present on March 30th, 1861, when Sarah Mapps Douglass—no relation to Frederick—delivered a lecture on the circulatory system of plants and animals to a "crowded house" where "she held her audience spellbound for an hour or more."

Mapps Douglass was a colleague of Catto’s. They both taught at the Institute for Colored Youth (ICY) near 7th and Lombard, one of the most selective schools in Philadelphia. Catto first came to ICY as a student, graduating in 1858, and later became ICY’s principal. It was likely there that he first met his fiancé, Caroline LeCount, an 1863 graduate who later became an educator and activist, and who along with Catto worked to desegregate the city’s streetcars.

Extant ICY records, including handbooks, can be found at the Library Company of Philadelphia. So can a photograph of Catto, along with compelling pictures of other mid-19th century men. Decades of the Christian Recorder can be found at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on microfilm, as can a poem Catto wrote to LeCount. There, we can also find letters written to Catto by his contemporaries, and others penned in his own hand. We can see teaching notes scribbled by his best friend, fellow ICY teacher Jacob C. White Jr., and we have another glimpse into Catto’s life as an athlete through records and scorecards of the Pythian "Base Ball Club" he founded with friends after the Civil War. Both the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania boast a trove of other resources that give us context and understanding into the life Catto lived.

However, the Free Library of Philadelphia is the best starting point, with Catto’s biography and other books about 19th century African-American life in Philadelphia among its stacks. For more research, you can visit Temple University’s Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection for context into Catto’s times. You can also access a digital exhibition curated by Judith Giesberg at Villanova University, A Great Thing for Our People: The Institute for Colored Youth, which among biographies and photographs, has a clickable map with key places in the African-American community, such as the churches listed above.

But this map includes another crucial establishment among blacks in 19th century Philadelphia. South of the Seventh Ward, at what is now 19th and Snyder but was then past Philadelphia’s neatly gridded streets, was Lebanon Cemetery. Founded in 1849 by Catto’s best friend’s father, Jacob C. White Sr., this burial ground became Catto’s resting place. On October 10, 1871, a contentious election day of racially-charged riots, Catto was assassinated.

Within the Library Company of Philadelphia’s collections, there is a beautiful pastel picture of Lebanon Cemetery. It shows a stately chapel, a sweeping willow tree, lush pine and maple trees, and people strolling its grounds. This seems a fitting and reflective place for Octavius Catto to be buried after 5000 mourners watched his funeral procession travel down from Broad and Race all the way to Snyder in honor of him. Catto’s remains were later moved to Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania, just outside Philadelphia, when the burial ground closed to make way for homes. What was once Lebanon Cemetery is now a primarily African-American neighborhood. Snyder Avenue, a major thoroughfare, is heavy with traffic, raucous with the sound of children playing on the sidewalks of their narrow South Philly streets. At night, laughter wafts from the open windows of two craft beer bars, which recently opened nearby, among the corner stores and tightly-packed row homes. This place is changing once more.

Just as whom we choose to honor is changing. At City Hall, a statue of Octavius V. Catto is being unveiled on Tuesday, September 26 at 11:00 a.m.. Around the country, other memorials have been shrouded, removed, torn down. If we want to learn more about the legacy of Octavius V. Catto, perhaps Philadelphia’s sculpture by Haitian born artist Branly Cadet might be where we end—but it could also be where we start. In this artistry, Catto’s palms are held open. His chest is lifted high and proud. His expression is calm and resolute. He walks forever in our city.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.