The Free Library of Philadelphia's Fleisher Collection of Orchestral Music at Parkway Central Library is the largest lending library of orchestral performance material in the world. Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection, hosted by Kile Smith and Jack Moore of WRTI, uncovers the unknown, rediscovers the little-known, and takes a fresh look at the remarkable treasures housed in the Fleisher Collection. Discoveries airs on the first Saturday of each month on WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia and online at wrti.org. Encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series air every Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. on WRTI-HD2. For a detailed list of all shows, please visit the Discoveries archives.

Saturday, January 12, 2013, from 5:00-6:00 p.m.

Charles Tomlinson Griffes (1884-1920). Bacchanale (1913, orch. 1919). Seattle Symphony, Gerard Schwarz. Delos 3099, Tr 11. 4:24

Griffes. The White Peacock and Clouds from Roman Sketches (1915). Solungga Fang-Tzu Liu, piano. Centaur 2971, Tr 1, 3. 10:18

Griffes. The White Peacock and Clouds from Roman Sketches (orch. 1919). Buffalo Philharmonic, JoAnn Falletta. Naxos 559164, Tr 1, 6. 9:45

Griffes. Poem for Flute and Orchestra (1918). Scott Goff, flute, Seattle Symphony, Gerard Schwarz. Delos 3099, Tr 7. 11:29

Griffes. The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan (1912/16). Buffalo Philharmonic, JoAnn Falletta. Naxos 559164, Tr 11. 12:29

Impressionism is an imprecise, even controversial term, the first “impressionist” Debussy having none of it. Each of its elements—open form, reliance on tone color over melody, unpredictable harmonies with modal scales—is challengeable, and Debussy’s music is awash with counter-examples. But everyone agrees that impressionism, whatever it is, exists, and that it is French.

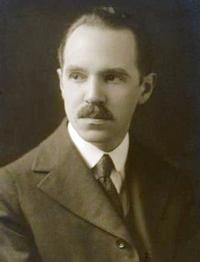

Which is why it is such a surprise that one of the leading impressionist composers lived and died in upstate New York and studied in, of all places, Germany. Charles Tomlinson Griffes was born in Elmira in 1884, studied piano with his sister, and then with Mary Broughton at Elmira Female College. Elmira is justly proud of this institution. In 1884 Mark Twain was in town, finishing The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; his wife was an alumna of this first baccalaureate-degree-granting college for women (her father being a founding Trustee).

Broughton paid for Griffes to study in Berlin, so taken was she by his talent. He intended to be a pianist, but gravitated toward composition, finally studying with the leading opera composer of the day, Engelbert Humperdinck. It’s easy to forget, because of the tunefulness of Hansel and Gretel, how avant-garde Humperdinck was. He influenced Schoenberg, and his natural vocal writing must have been a model for Griffes.

Back in America to support his recently widowed mother, Griffes accepted a job teaching music at the Hackley School in Tarrytown. While he chafed a bit at the relative obscurity of his position, he could compose, so to songs written in Germany he soon added piano and orchestral works. Picturesque titles were sometimes just that, with no stories behind them, but the works are delicate, free flights of a brilliant imagination. Bacchanale and Roman Sketches he orchestrated from the original piano versions for 1919 premieres with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski conducting. He did the same with his most famous orchestral work, The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan, based on the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor poem. Pierre Monteux conducted it in Boston in 1916.

The Poem for Flute and Orchestra has long been a repertoire piece for flutists. It received its first hearing with Georges Barrère, one of the leading flutists of the day, who performed it with the New York Symphony Society under Walter Damrosch. It seems that Tarrytown wasn’t so out-of-the-way, after all. Premieres in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, with a dazzling, growing body of music and with new harmonic adventures hinted at—we wonder how far Griffes, always sickly, would have gone if he hadn’t died of influenza at age 35.

Georges Barrère’s role is interesting. In 1894 he sounded the very first note in a piece Pierre Boulez called the awakening of modern music. While Griffes was still learning the piano, Barrère played that haunting flute opening in the premiere of Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. Impressionism may be hard to define, but draw a bright line from Paris to Elmira to Berlin to Tarrytown, then smile at the genius of Charles Tomlinson Griffes.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.