A Collection of Musick Adapted for the Harpsichord ex Libris Michael Hillegas

By Del-Louise M.My name is Michael Hillegas, and if you know me, it’s most likely because I served as the first Treasurer of the United States from 1777-1789. I have always, as you may have surmised, had close ties to Philadelphia. After all I was born, and spent much of my life here. So imagine how excited I was when I found out that I still have connections, and at the Free Library of Philadelphia (FLP) no less! Firstly, Laura J. Stroffolino, presently a librarian in the Catalog Department at FLP, is my cousin through my uncle Johann Friedrich, best known for having challenged Johann Phillip Boehm, a Reformed minister who played an instrumental role in planting the German Reformed Church in America. However, in 1727 when my uncle questioned his qualifications to preach in several Reformed congregations, Boehm was not yet ordained. He never forgave this, and even as late as 1744 was complaining about it in official letters to the Classis at Amsterdam. This is a governing body of pastors and elders of the Reformed church having jurisdiction over our local churches. In the course of his July 8, 1744 (#38) report Rev. Boehm mentioned that “Whereupon after that time Frederick Hillegas arrived in this country with a companion. He also had two brothers, called Peter and Michael, living at Philadelphia, but he himself lived at New Goshenhoppen.” Michael was my father, so now posterity knows how we’re all family. I’d like to dedicate the rest of my thoughts penned here to Laura and all of our common relatives.

My other connection to the Free Library of Philadelphia is my Music Arranged for Harpsichord, a manuscript that I kept from July, 1747 to 1754 or so, and which Henry Stauffer Borneman saved from obscurity by adding it to his Pennsylvania German collection of Fraktur, imprints, and manuscripts. When Mr. Borneman died in 1955, FLP was able to buy this exquisite collection, which reflects the essence of Pennsylvania German art and culture. So, my music book is now labeled Borneman Manuscript 144, and, thanks to a 2011 grant from the prestigious Save America’s Treasures program, a select number of these manuscripts will soon be restored to pristine condition, and digitized for online access. I’m hoping mine will be among them.

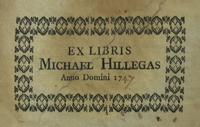

I was eighteen when I first started keeping the Harpsichord book, and was quite proud of my musical accomplishments, so I had a special label printed that you’ll find at the one end of the book on the inside cover EX LIBRIS MICHAEL HILLEGAS Anno Domini 1747. I couldn’t resist having another label, to be found at the other end of the book on the inside cover and written in my hand: A Collection of Musick adapted for the Harpsichord &c. with a downturned ear on which I wrote in mirror image M. Hillegas, His Book, July 1747.

People are always quoting what John Adams says in his diary about my musical interests: “Hillegas is one of our Continental Treasurers, is a great Musician—talks perpetually of the Forte and Piano, of Handell, &c. and Songs and Tunes. He plays upon the Fiddle.” Had we ever had a chance to talk upon the subject, I would have told Adams that my father insisted I follow him in his business as a merchant, but also encouraged me to study music, for it was the one thing in life I lived for.

If you’re a Hillegas, you never do anything half way. Thus, as you’ll see from my Harpsichord book, I learned musical theory, also how to play a thorough-bass, which is a musical shorthand used by keyboard players during my day to indicate intervals, chords, and non-chord tones in relation to a bass note. With this “figured bass” we were able to add the proper chords to the melody, and improvise where needed. You can’t play a harpsichord without tuning it, so I included Instructions for Tuning as well, and became a master tuner.

You’ll find my hand-drawn picture of a clarinet with a fingering chart, an additional illustrated finger-chart for a clarinet with four keys, which I later tipped in—an insert, which I pasted to a page of the book, along the binding margin, and a hand-drawn picture of guitar frets with the scale of the guitar. Obviously, I was more than casually interested in both instruments. I don’t know why, but I only included fragments of some parts for clarinetto and Violino from a Minuet—a slow, stately dance in triple meter which is presently quite popular—by Mr. Humphreys, an English composer and violinist, who died in 1733 when only 26.

As to other music I collected, you’ll find George Frideric Handel’s Water Piece, a collection of orchestral movements for orchestra, written for a festival that took place on July 17, 1717 at the request of King George I on boats on the Thames River in England. Also, you’ll find a Hornpipe in 4 variations by him. A Hornpipe, of course, is a dance. Mr. Handel was so fond of its rhythmic aspects that he used it as the tempo marking alla hornpipe in his Water Music, No. 12. Mr. Handel also set Mr. Lochman’s charming verses in the song The Request to the Nightingal.

There are also some country dances such as The Man in the Moon, On Ev’ry Hill, and I’ve got a Wife of my ain’. These are mostly Scottish, and you need a good Scottish fiddler to do them justice. Also of this ilk are Prince Eugen’s March Tune, The Highland March, and King George’s Minuet.

Then there’s Bright Author of my Present Flame, words by Allan Ramsay and set by Mr. Travers, an English composer and organist to the Chapel Royal in 1737. You might recognize The God Vertumnus lov’d Pamona fair for voice and instruments set to music by Charles John Stanley in 1748. Blinded when he was two years old, Mr. Stanley is an astonishing musician, and I must say I’m quite fond of this piece.

I also made a copy in my book of The Miller’s Wedding, which was sung by the character Mr. Beard in Harlequin Ranger, a pantomime produced and performed by the actor Henry Woodward at Drury-lane, London in the 1751 season. It’s quite jolly.

Adolph Charles Kunzen’s Minuet taken from his Sonatas for Harpsichord Opus 1 is quite enjoyable to play. Kunzen comes from Germany but lived in London from 1754 to 1757. His 12 Sonatas for Harpsichord were dedicated to the Prince of Wales, and since then have been published as Opus 1. He also has written an excellent thorough bass tutor. Of course, there are other pieces from my Harpsichord book, which I’ll share with you another time.

May I mention my former teacher Mr. John Palma, who some people say was the first to give a public concert in Philadelphia on January 25, 1757? I rather think I made a note in my Harpsichord book that I took my first lesson on January 3, 1754 with Mr. Palma, and at the following lesson paid him two Guineas. I also marked off how many lessons I took and paid, which were forty I believe. Also, if my memory serves me correctly, there were an additional twenty-one lessons, which I did not mark as paid.

My father taught me that you should always take an opportunity and turn it into a profit. When he died in 1749, I took over his business, and using the entrepreneurial skills I had learned working in his counting house, increased the family sugar refining and iron manufacturing interests quite handsomely. It will also not surprise you that I used my musical knowledge, performance training, and my business know-how and connections to open the first music store in Philadelphia, operating from my home in Second-street opposite Samuel Morris, Esq. On December 13, 1759, I placed an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette letting it be known that I had

an extraordinary good and neat harpsichord with four stops; a good Violoncello; an Assortment of English and Italian violins, as well common ones as double lined, of which some extraordinary; a Parcel of good German flutes, imported here from Italy. Also imported in the last Ships from London, a large Assortment of Musick, of the best Masters, vis., Solos, Overtures, Concerto’s, Sonata’s and Duets, for Violins, German Flutes, Hautboys, French Horns, Violoncellos, and Guittars, Volontaries and Lessons for Organ and Harpsichords, ruled Paper of various sizes for Musick, and Musick Books, Tutors or Books of Instructions to learn to play on the Violin, German Flute Hautboy or common Flute without a Master, Song Books, Cantatas, Songs in Sheets and a choice Parcel of Violin Strings &c.

If you look at other additional Pennsylvania Gazette music advertisements such as those of January 5, 1764, May 21, 1772, and June 19, 1776, plus some of the request orders I sent to the London publisher John Johnson in 1760, you’ll note that I was quite successful and knew what I was about. I knew my product, and my clientele. I personally was familiar with the music and its composers, and the instruments upon which the music was played. I also knew the local music and dance masters, and they in turn introduced my music shop to their students. So, you see there was no lack of customers, but quite the opposite.

Everywhere I went I followed my father’s advice, and took advantage of the moment, and what it offered me. I value what a man can do for himself and others if free to dispose over his own property thus earned by ingenuity and his own wits.

During the Revolutionary War when America desperately needed financial support, I chose to donate or loan moneys in support thereof. In fact, so deeply did I care about the future of this land that I gave almost all of my assets to the cause. Since I had been selected in 1775 by the Continental Congress as co-treasurer of the colonies, in 1776 Continental Treasurer, and then in 1777 assumed the title Treasurer of the United States, I saw the need first hand. During this time I came into contact with many men who valued music as I, and wherever I could serve them I did. Thus, in 1776 I added A Complete Tutor for the Fife to my shop inventory for more fife players would be needed as the war progressed. I had other instruments in the shop ready to supply the military bands as needed. It also was my pleasure to serve Mr. Thomas Jefferson in his musical needs between 1775-1779 for printed music, violin strings, guitar strings, and a violin mute. Some find it quite singular that my music shop was apparently the only one of its kind in all of the Colonies prior to the American Revolution.

Please know that I continued making music as well as selling it. I remember offering to play my violin in a chamber orchestra at a funeral in 1776. Frances Hopkinson will tell you that several of us played in 1778 for a Court of Music at Mr. Brown’s at the Navy Office. There were many other occasions as well, too numerous to mention. However, I hope you can see that music is and always will be part of my life, and that I have been successfully involved with it artistically and commercially since the days of my youth. My Harpsichord book, that is, the Borneman Manuscript 144 is proof of this and a valuable witness to all who require documentation of my passion and love for the art of music.

Please be sure to visit our Facebook gallery for more images of the Michael Hillegas Music Arranged for Harpsichord, Borneman Manuscript 144.

Preservation of the Free Library of Philadelphia's Pennsylvania German manuscript collection has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Because democracy demands wisdom. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.