by Edward Pettit

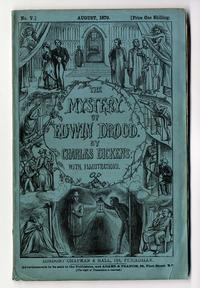

Tonight our Dickens Literary Salon will be discussing the author’s final, incomplete mystery novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. SPOILERS AHEAD

When Edwin Drood goes missing it is assumed that he has been murdered. Edwin’s uncle and guardian, John Jasper, is the choirmaster of the Cloisterham Cathedral, but Jasper is also secretly in love with Edwin’s fiancée, Rosa Bud. To cast further suspicion on Jasper, he is also an opium addict, often visiting the squalid opium den of Princess Puffer. However, many of the other characters in the novel are unaware of Jasper’s secret lives, and when Jasper casts aspersions on Neville Landless as the killer of Edwin, some readily believe it. Enter into the town of Cloisterham, one Dick Datchery, a white haired, eccentric newcomer to the town, who seems to be investigating the disappearance of Edwin. Unfortunately, at this point in the novel, Dickens died, leaving his readers with just half the novel complete and all the mystery still to solve.

For more than 140 years, various authors and critics have tried to solve the mystery. At our Dickens Literary Salon, we’ll do the same. But just over forty years after Dickens death, some readers assumed Jasper must have murdered Drood, so they put him on trial. On January 7, 1914, The Trial of John Jasper, with eminent writer and Dickens critic G.K. Chesterton as judge, George Bernard Shaw as foreman of a jury that included such writers as W.W. Jacobs and Hilaire Belloc, was held at King’s Hall, Covent Garden. The proceedings were published and you can read the transcript of the trial here: http://www.archive.org/details/trialofjohnjaspe00jasprich.

The participants in this mock trial agreed beforehand that Mr. Grewgious could not be called as witness by either side (lucky for the defense) and that hearsay evidence would be allowed. Opening statements were read and witnesses called: Durdles, Crisparkle, Helena Landless, Princess Puffer, Bazzard (who in this trial is assumed to have been Datchery in disguise).

At the close of the trial (after four hours and twenty minutes), the jury revealed that they had already come up with their verdict during the luncheon period: Jasper is guilty of Manslaughter, but not murder because no body had been found. I love the way it all ends:

The Prosecutor: I should like to urge that the Jury be discharged for not having performed their duties in the proper spirit of the law. We have heard from the Foreman that the verdict was arranged in advance, and I decline to accept that verdict, and ask for your Lordship's ruling.

The Foreman (GB Shaw): The Jury, like all British Juries, will be only too delighted to be discharged at the earliest moment: the sooner the better.

Mr. Chesterton: I want to associate myself with my learned friend.

Judge: My decision is that everybody here, except myself, be committed for Contempt of Court. Off you all go to prison without any trial whatever!

Just a few months later, the Philadelphia Branch of the Dickens Fellowship decided to hold their own trial of Jasper at the Academy of Music on Apr 29, 1914, as a charity benefit for various hospitals This trial was presided over by an actual judge, PA Supreme Court Justice John P. Elkin. The Attorney General of Pennsylvania and another judge were prosecutors and a congressman represented the defense. George W. Elkins (the father of William McIntire Elkins, whose library is preserved in the Rare Book Dept of the FLP) was a member of the jury.

You can read it here: http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013472489. The book also contains photographs of the participants.

The Philadelphia trial acknowledges the British trial adjudged by Chesterton, however Jasper had since escaped to America where he was caught and will now be retried in an American court of law. Also, according to the introduction of the published transcript, the British trial of Jasper “instead of satisfying the public, only left confusion more confounded and added to the uncertainty already existing. Not only did the English people declare that the verdict meant nothing, but the entire Dickensian world protested that Jasper should have been convicted of murder, or else acquitted. He was guilty, or not guilty, and a verdict in the Pickwickian sense would never do, even if Bernard Shaw were foreman of the jury which rendered such a verdict.”

The Philadelphia trial began with the choosing of the jury. Some prominent literary Philadelphians not chosen from the pool were Ellis Paxson Oberholzer, A.S.W. Rosenbach, and Charles Sessler.

The very funny proceedings are rife with in-jokes for those familiar with the novel. When the first witness, Canon Crisparkle, is called by Mr. Bell, the Prosecutor, Mr. Sapsea objects:

I protest against the Canon taking the stand, sir. I am the first citizen of Cloisterham.

Mr. Bell: Do you insist upon your prerogative, sir?

Mayor Sapsea: I do, most positively.

Mr. Bell: All right, Dogberry, take the stand.

(Mayor Sapsea takes the witness stand.)

Mr. Bell: What quadruped in the animal kingdom do you and Dogberry typify?

Sapsea: Not a jackass, like counsel.

After a five-hour trial the jury retired three times to deliberate: 6-6 tie, 9-3 for acquittal, and finally 11-1 for acquittal. After all, no body had ever been discovered. The American jury did not believe Jasper could be convicted without first proving that Drood was really dead.

Tonight, at our Drood Literary Salon, we won’t hold a trial (I have to agree with the Philadelphians: where’s the body?), but we will, Datchery-like, tramp the streets of Cloisterham to discover what happened to Edwin Drood. Was he murdered? Who could have done it? Join us as we investigate (and solve?) the mystery of Edwin Drood.

Edward Pettit writes about his adventures in Dickens at http://readingcharlesdickens.com/

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.