Abortion and Women's Rights 1970: Film Screening and Panel Discussion

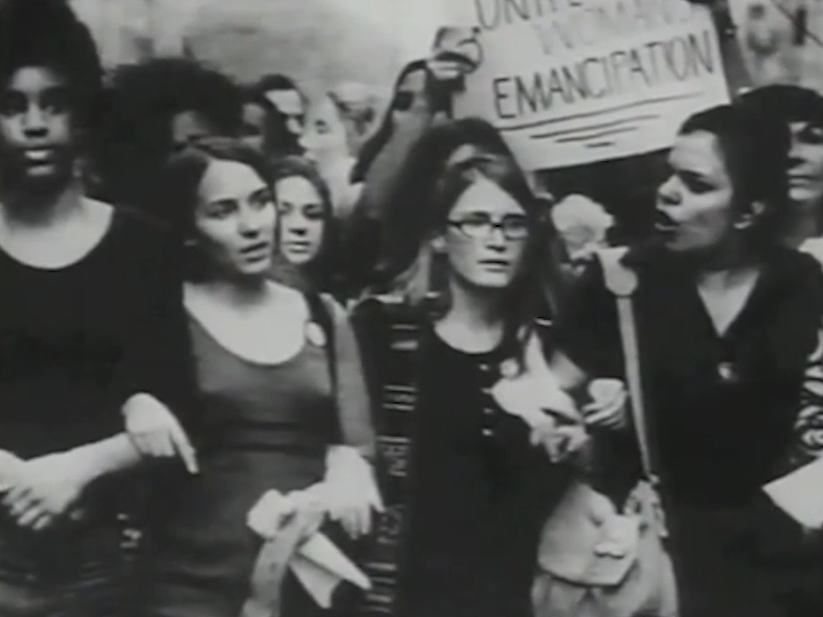

By Ben R.On Tuesday, January 21, at 6:00 p.m. the Social Science and History Department will screen Abortion and Women's Rights 1970, the first documentary made in the U.S. about the struggle for reproductive rights. Following the 28-minute film, there will be a panel discussion about the film, its historical context, and its relevance to the present day.

Registration for the screening and discussion is encouraged, but not required.

Mary Summers, a Senior Fellow with the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania, co-directed the film 55 years ago. She spoke with the Free Library about the film, its context, its relationship to the present, and the panel she assembled to discuss it on the 21st.

What led you and your co-directors to decide a film like this would be an important intervention in the abortion debate at the time?

Our basic goal was to give women a chance to tell their stories about what they went through in seeking abortions in a way that would be useful in the state-by-state efforts to legalize abortion at that time. Colorado legalized abortion in 1967, but only in extraordinary circumstances like rape and incest. Other states were debating whether to do so and with what restrictions. Jane Pincus, whose husband had worked on documentaries with the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, started this project after she heard a radio program about the debate over a bill to legalize abortion in Massachusetts. Most state representatives at that time were men, and every voice she heard in that debate was a male voice. The bill was defeated. She thought a documentary would be a way to bring women’s voices into those debates. There were very few women filmmakers at that time, so those of us who decided to work with her on this project also saw learning how to use cameras and recordings and editing machines as a way both to make women’s voices heard and to make a difference in a world where access to safe abortions could make such a difference in people’s lives.

As a public library, we’re interested in preserving cultural memories. What do you think the film can say to an audience in 2025 about 1970?

We made the film in the context of the Women’s Liberation Movement of that era. We — and many of the women in the film — were also active in the Anti-War Movement and struggles for civil rights, decent jobs, healthcare, and welfare rights. Women in the film speak to their frustration with male doctors and legislators — and the lack of money — that denied them access to birth control and safe abortions. They also speak to the reality that most women who died from illegal abortions were poor Black and Latino women. They speak out against forced sterilizations and drug testing on third-world women as well as support for women who want to have children. My hope is that the film will encourage audiences in 2025 to think about the strengths as well as the limitations of the efforts of those times to build a movement addressing all those issues in what was, at its best, a spirit of solidarity.

So much has happened with this issue since you made the film, and yet we’re back to a world where abortion is inaccessible in many parts of the country. How have you seen activism around this issue change in the past 55 years?

After the Supreme Court declared a constitutional right to abortion in its Roe V. Wade decision in 1973, the movement to support abortion rights and access developed an increasingly professional focus. Medical providers opened abortion clinics. Lawyers fought restrictions to abortion access in the courts. In this new context, researchers and entrepreneurs made possible today’s reality where every pharmacy offers pregnancy tests over the counter, and many people with insurance who are up to 11 weeks pregnant have access to virtual appointments and medical abortions in their homes. Making these options available to people who have the resources to use them has made a huge difference. Non-professionals no longer have to train each other to perform surgical procedures in apartments in order for tens of thousands of women to obtain abortions in the way that the Jane Collective did in Chicago in 1970.

But these developments have failed to serve many vulnerable people who do not have the economic resources and connections necessary to take advantage of them. In addition, decades of a relatively narrow, professional, court-focused approach to defending abortion rights and access have been associated with less organizing, less public debate and engagement, connecting the need for abortion access with the many other issues impacting people’s lives, families, health, and opportunities in a society that has become more and more unequal.

These trends meant that abortion rights and access became increasingly vulnerable in the 1980s, a time when conservative religious leaders and politicians encouraged the growth of an anti-abortion movement. This movement conducted local, state, and national campaigns appealing to many people’s fears that in an increasingly commercial, deregulated society, the value of life was being trivialized. Demonizing abortion clinics as making money off murdering babies, this movement also gave rise to violent, misogynistic trolls who made it increasingly dangerous both to work in abortion clinics and to take public positions in support of abortion rights. The result was an increasingly vicious cycle that closed clinics, put defenders of abortion rights on the defensive, and in 2022 resulted in a Supreme Court that overturned Roe, thereby giving the states permission to once again make abortion illegal.

The one silver lining to these huge losses and defeats is that they have resulted in more and more efforts to mobilize popular support and engagement with defending abortion rights and access. Referenda and constitutional amendments have passed in most states where they have been on the ballot; abortion rights and care organizations throughout the country are also organizing support for individuals faced with seeking abortion in increasingly difficult circumstances. But it’s still clearly the case that there’s a lot of work to be done.

You put together a fantastic panel to discuss your film. Tell us a little about how you chose the panelists.

My goal for this panel was to find people who could make connections with the struggle for women’s and abortion rights and access in 1970 and tell us what that struggle looks like today. The panel includes the Interim Executive Director of the Abortion Liberation Fund of Pennsylvania, an organization that provides support, financial resources, and information to individuals seeking abortions in our state; a law professor; a lawyer; and a historian; who are all in different ways engaged with stories of women seeking abortions, both past and present, and struggles to defend their rights. I am looking forward to learning a lot from all of them!

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.