Updated Wednesday, September 30, 2020 4:45 p.m.

The census deadline, originally slated for September 30 after the federal administration moved to an earlier date, has now been extended to October 5.

In 1930, Dorothy Evelyn Hudson lived in a rented home on an unimproved dirt road in Fairfield County, South Carolina with her uncle, aunt, and their four-year-old son. Dorothy, age eleven, was the eldest of her siblings, having two little brothers and two sisters all neatly stacked in years from ages four to ten. But she wasn’t the oldest child in the household—a fifteen-year-old cousin, Berkley Belton, also lived on the farm. Dorothy’s aunt and uncle could read and write, but they never attended school, and neither had her teenaged cousin. But Dorothy and her siblings, save for the youngest, did attend school. Like many of their neighbors, the Beltons and Hudsons were Black.

Dorothy didn’t always live with her aunt and uncle. When she was a few months shy of her second birthday and her sister Annie just a baby, she lived with her parents, a young couple by today’s standards. Dorothy’s father John was 26, and her mother Bertha was 22. They too, like Bertha’s brother David, rented a home on a farm in Fairfield County, not far from the Beltons.

All of what I know I have pulled from census reports.

The 1920 and 1930 censuses give me hints as to my grandmother’s childhood, for Dorothy Evelyn Hudson was my father’s mother. They tell me where she grew up, and clue me in on what her life might have been like; full of farm chores, but perhaps not abundant with money or financial resources. They even tell me the Hudson family was light-skinned. These census reports give me information to glean more information from. They’re a vital piece of tracing family history.

They do not tell me everything. I don’t know exactly how long Dorothy Hudson lived with her aunt and uncle, nor her relationship with them, although I can guess that with the households not far from one another, Dorothy knew her aunt and uncle well. I know she likely lived with them out of necessity, as her father died in 1929. I can infer that David Belton may have offered to take in his sister’s children, just as he’d taken in another nephew, the teenager Berkley.

The census doesn’t tell me that my great-grandmother Bertha Hudson woud have grieved the death of her baby Donald, Dorothy's twin. It doesn’t tell me that Bertha was a frugal parent, sewing her children’s clothing from flour sacks. It doesn’t leave with me the shock and panic she must have felt when she learned her husband, handsome and fit in his late-thirties, suffered a heart attack and died at a construction site in downtown Columbia. Much of this I learned before I was in my twenties when Grandma still lived, or from the family historian, my Aunt Bert, named for Bertha Hudson. Still, even Aunt Bert didn’t know that her mother once stayed with extended family for however long—but with enough feeling of permanence that when a census reporter came to the Belton’s door, either David or his wife named their five nieces and nephews as living with them. It seems my grandmother never thought to mention it.

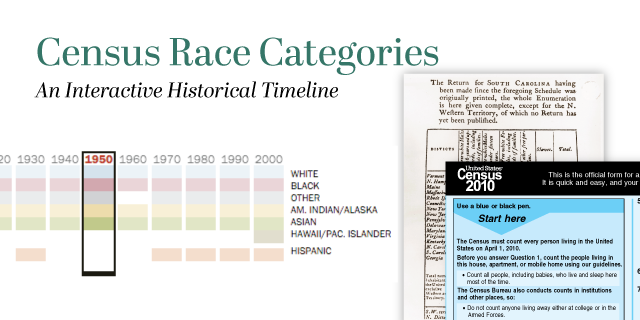

Census reports don’t always tell the whole story of course, nor do they tell the whole truth. Ages listed are commonly off by a few years. Census takers, in a time of handwritten ledgers, were notorious for abbreviating or misspelling names. And race has always been a fraught category. "Mulatto" was a category in the mid-late 1800s, and again in 1910 and 1920 (that year, my grandmother’s family was listed as “Mulatto”). A modern reader might know this as a derogatory term for someone who is biracial, which can be misleading if you’re using census reports to infer an ancestor’s parentage. But here, "Mulatto" simply meant light-skinned, non-white people and sometimes included Native Americans.

But many Native Americans were never counted at all. An "Indian" category was added in 1860, but enumerators only counted indigenous people who lived in or near white communities, or those they otherwise considered "assimilated." And in 1900, census enumerators were charged with guessing the percentage of a Native American person’s white versus indigenous blood. Even as late as 2000, the United States government wouldn’t fairly provide listings for biracial and multiracial people. People were told to check off the race they most identified with and couldn’t mark more than one race category. This year, in 2020, the federal census still hasn’t gotten it fairly. Many are forced to misgender themselves, with gender nonbinary people only able to choose "male" or "female."

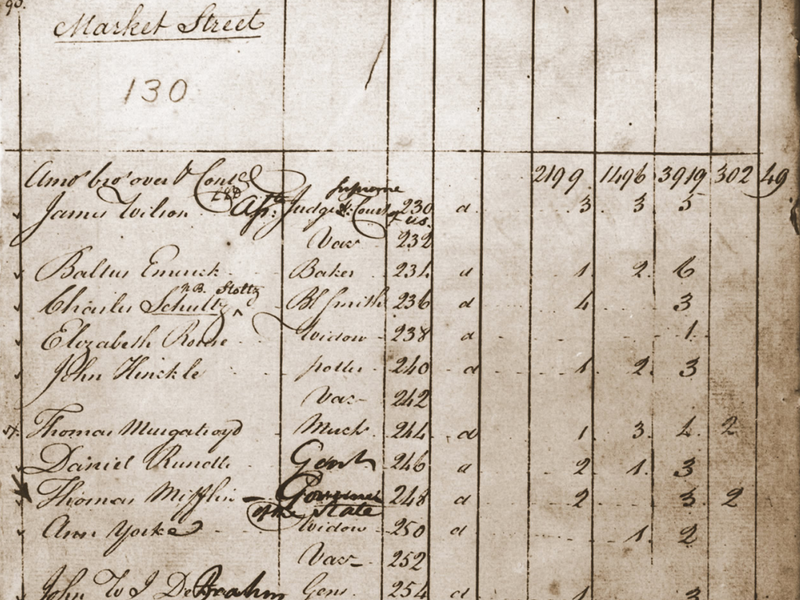

A census enumerator's records from the 1790 census, the first-ever to be conducted in the United States. (National Archives)

But even at the advent of the U.S. census in 1790, the nuances of race and gender have historically been erased. Then, it was a barebones sketch of the head of household’s name, as well as the number of free white males older than sixteen; free white males under sixteen; free white females; all other free persons; and slaves. Thus, women’s names usually were not listed, and free African Americans were not always enumerated by age or even gender. Enslaved people were counted as the mere property that they sadly were.

Missing in action are the census reports from a century later. Almost all of the 1890s census reports—by then with much more detailed information—burned in a fire at Washington D.C.’s Commerce Department in January, 1921. Of the 62,979,766 people enumerated in 1890, the records of only about 6,000 survive. Most of us, if using the U.S. census to trace our ancestry, will be thrown off the historical trail at this juncture.

The most recent documents the public has access to is the 1940 census. That year, Dorothy Hudson was in her early 20s, living at 912 Pine Street in Columbia, South Carolina with her mom and all of her siblings except Annie, who was married. Her mother was a cook in a private home, reporting her earnings at $412 a year—less than some of her neighbors who were laborers and domestic workers, but more than many others. But Dorothy didn’t stay home for long. Soon, she herself was a mother, becoming Dorothy Williams when she married a smart, slight young man with a slow, tenor drawl, named Hubert.

This year, we only have until October 5 to take census, which can be done online or by phone. The census helps determine federal funding of communities and to draw political districts, but individual information about you or your household cannot be shared to any outside agency, not even law enforcement. So it’s vital that we fill it out.

Census reports are kept under cyberlock-and-key for 72 years, and we all know that in seven decades, many of us who are reading this piece will be long gone. But the census is the story of us, a gift we can leave to our kin. Because like my grandmother moving in with her extended family after her father’s death—which I would have never been aware of without the 1920 census—who knows if there are pieces of our lives we’ve never thought to share?

Through October 5, we need your help to make sure that every Philadelphian, every Pennsylvanian, and everyone living in the United States is counted in the 2020 Census!

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.